2015-10-13 By Ed Timperlake

The Chinese are in the process of an island-building spree in the South China Sea.

And Chinese Admirals have claimed that it is the south CHINA sea after all. “The South China Sea, as the name indicated, is a sea area.

“It belongs to China,” said Vice Adm. Yuan Yubai, who commands the North Sea Fleet for the People’s Liberation Army Navy.”

As the Chinese position themselves in an effort to expand launch points for their forces, the U.S. does not need to sit idly by.

Not only is the US Navy more than capable of challenging Chinese actions, but on the diplomatic and political military front, this is an appropriate time to augment Taiwan’s defenses and more effectively integrate it into a deterrence depth strategy which the U.S. and its allies are shaping to deal with threats in the region.

The PRC is seriously misreading the US Navy, as well as the joint and coalition forces in the region.

Unfortunately, the dictators of Beijing seem to believe what some writers in the U.S, have saying, rather than what the US Navy is capable of doing.

Typical of seriously flawed logic which reinforces Chinese miscalculations, in a July 11, 2011 a story about the improving military capability of the Peoples Republic of China — “China’s ‘eye in the sky’ nears par with U.S.” — a Professor at the US Naval War College symbolically rowed ashore and surrendered her sword to the PLA forces.

“The United States has always felt that if there was a crisis in Taiwan, we could get our naval forces there before China could act and before they would know we were there. This basically takes that off the table,” said Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor at the US Naval War College in Rhode Island.

History shows the fighting Navy with modern 21st Century weapons and systems might think otherwise.

And connecting innovation in U.S. forces with those of allies in the region, including Taiwan provides a real opportunity to reshape misguided Chinese thinking.

Rick Fisher, a Senior Fellow on Asian Military Affairs at the International Assessment and Strategy Center, nails it on the need for strong capable 21st Century Technology in the Pacific to deter war.

“Washington gains nothing by delaying the sale of new F-16s to Taiwan. Selling new F-16s with modern subsystems will more quickly prepare the Taiwan Air Force for what it really needs, a version of the fifth-generation F-35. Depending upon the equipment package, upgrading Taiwan’s early model F-16s can sustain a low level of parity, but that will not keep pace with a Chinese threat that grows every day,” Fisher said.

The statement in a global newspaper from the Naval War College by Professor sends the exact opposite signal. One which does not comport with US policy and behavior in the region for more than half a century. We have seen this play before, whereby the forces of Imperial Japan assumed US weakness and inability to respond to a superior race.

But this miscalculation, which the Chinese are clearly repeating, needs to be put in an historical context.

Less than a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the “Doolittle Raiders” had their “30 Seconds Over Tokyo” bombing raid and in doing so the Navy-Army Air Corp team gave the Japanese leaders a real wakeup call that they would ultimately lose WWII. B-25 Army Air Force crews made their heroic flight launching from the deck of the CV-8, USS Hornet.

After the Doolittle Raid, the USS Hornet continued to fight the Imperial Japanese Fleet. At the Battle Of Midway the entire complement, save one pilot, of Torpedo Squadron 8 from the Hornet were all killed, but the great miracle at Midway victory was achieved.

Finally, the heroic ship was sunk at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Island. Quoting various reports about the battle proved that it was a hard ship to kill.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Hornet_%28CV-8%29

In a 15-minute period, Hornet took three bomb hits from “Val” dive bombers, another bomb hit compounded by the “Val” itself crashing into the deck, two torpedo hits from “Kates”, and another “Val” crashing into the deck. Because of the damage the Hornet was taken under tow when another Japanese plane scored a hit.

The order was given to abandon ship. U.S. forces then attempted to scuttle Hornet, which absorbed nine torpedoes and more than 400 5 in (130 mm) rounds from the destroyers Mustin and Anderson. Mustin and Anderson moved off when a Japanese surface force appeared in the area.

Japanese destroyers Makigumo and Akigumo then finished Hornet with four torpedoes. At 01:35 on 27 October, she finally sank with the loss of 140 of her crew

It was the last US fleet Carrier to be sunk in WW II.

And another history lesson this time from my class in Naval History over four decades ago at the US Naval Academy.

I have tried to find the original source but I just remember the Professors narrative.

As the war in the Pacific got closer to the main Islands of Japan, Kamikazes — the “unmanned” vehicles of the day — were used to attack the American Battle Fleet. At that time the Aircraft Carrier was the primary ship leading the attack. Killing carriers was the goal. The Navy knowing this screened the fleet Carriers with radar picket destroyers to both give warning and provide anti-aircraft fire at incoming Kamikazes.

During a lull in after a wave of deadly Kamikaze attacks a voice was heard skipping across the waves-by sailors of the main fleet — sound can do this at sea. As told it was an Ensign on a radar picket ship and he was telling the crew that all the officers were killed but he was in command and they would continue to fight the ship—I was told the Destroyer was lost.

Memorial Hall United States Naval Academy captures the fighting spirit of the Navy/ Marine team and honors the names of those killed in combat since the founding of the Academy.

And from my regular attendance at the US Navy Capstone course, I can assure Americans, that the US Navy is producing officers worthy of the tradition of the US Navy.

Historians have debated the number of USN Ships sunk by Japanese Kamikaze attacks during all of WW II in the Pacific. Their counts vary from a low of 34 to a high of 47.

Compare that Kamikaze fight against a reactive enemy over a almost a four year war with a US Task Force caught in a Pacific Typhoon in one 24 hour period. In the Pacific Typhoon of December 18, 1944 three Destroyers capsized; the USS Spence, USS Hull, USS Monaghan, with the loss of most of their crew–over 700 hundred sailors perished. Additionally, 146 aircraft on Fleet Carriers were struck from the rolls because of damage.

In short, when the threat of being attacked from the air the US Navy has prevailed and triumphed.

The Fleet Moving Forward

There is a fundamental rule in tactical battles that all technology is relative against a reactive enemy. It is most often the intangibles of training, tactics, and developing newer and more capable technology that can win the final battle.

If PLA satellites are a problem and it is a choice between putting a Carrier Battle Group at risk or fighting a space war, I think the fighting Navy is capable and ultimately ruthless enough to blind the PRC military.

After the PLA shot down a satellite from a land based launch pad, the US Navy demonstrated our at sea capability-from a Department of Defense Report:

“At approximately 10:26 p.m. EST, Feb. 20, (2008) a U.S. Navy AEGIS warship, USS Lake Erie (CG-70), fired a single modified tactical Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) hitting the satellite approximately 133 nautical miles over the Pacific Ocean as it traveled in space at more than 17,000 mph. USS Decatur (DDG-73) and USS Russell (DDG-59) were also part of the task force.”

So let is make it simple for the PLA, PLAN. PLAAF and 2nd Artillery: the US Navy is battle tested with a legacy of carrying the fight to any enemy.

In the 21st Century it will be important that no platform fight alone. USN satellite killing Aegis ships will soon be joined by F-35Bs flying from the Navy/Marine Amphibious Readiness Group “Gator” Navy-the USMC F-35B V/Stol. This is a huge at sea multiplier in capability. Carrier Battle Group Air Wings with the F-35C will give Naval Forces afloat both situational awareness and the ability to fight a 3 Dimensional War.

Finally, like the radar picket ships of WWII, current Destroyers, and Frigates can add a huge defensive element against CHICOM incoming missiles. The capability to spoof and jam incoming guided weapons is an art of “tron war” practiced by Navy forces for decades.

Rather then unilaterally “take our forces off the table,” the 21st Century Navy can blind them and blast them-and that is real deterrence and should give the PRC pause before starting a hostile action.

Reinforcing Taiwanese Defense in Response to the “Wall of Sand”

If the “Great Wall of Sand” is being asserted as PRC “territory” then Taiwan should be highlighted as a free society nation whose culture challenges those of the Chinese authoritarians. Defending Taiwan is a key element for a deterrence in depth strategy being worked by the US with its allies in the Pacific.

Looking at the geography of what one might call the strategic quadrangle in the Pacific, it is clear that Taiwan plays a key role. It was no accident that the Japanese empire wanted to operate from Formosa and to use it as a key lynchpin in their power expansion.

The Republic of China owns a key dominant piece of Pacific Island real estate and it is imperative that now more than ever the U..S and the allies must not lose that Island cluster as part of a Pacific defense effort.

And the emphasis clearly is upon a defensive effort, and evolving technology provides significant advantages to do so.

In the 20th Century Taiwan had two key features of significance.

First, it was a template for a Chinese free open dynamic society, which must scare the PRC totalitarian leaders to their core, and this intangible is just as important today as it was years ago.

It is not about the PRC as currently constituted swallowing up Taiwan; it is about the democratic traditions, which have developed on Taiwan transforming the Communist state and leading to its collapse.

This is not just about geopolitics but also about the future of what kind of China plays what kind of role in the world.

Simply having seminars in Washington with the current class of Chinese Communist leaders will not lead to a better China or a better world.

In fact, the authoritarian regime uses seminars as part of its information war approach to the United States.

It is time to recognize the strategic opportunity of our own form of information war, namely democracy and Chinese can go together and can be defended in the form of Taiwan.

Second, if one looks only at 20th Century “stove piped” military thinking made up of discreet independent elements, an independent Air Battle, Sea Battle, and Big Army land war, then Taiwan was important. But true then, and even more significantly now, Taiwan lies at the juncture of effective Pacific DEFENSE.

With the US and the Allies evolving toward a “no platform fights alone,” AIR/SEA cross-domain joint Pacific defense, then it is essential that Taiwan stay aligned with the democracies.

Thankfully, if PLA wants to fight “feet wet,” the U.S. and Allies can still make them fight alone in the dark and die.

How long we keep this edge is a guess, but US forces do train rigorously and have realistic testing in the field and at sea. US and Allied technology with our better-trained and more combat experienced human elements appears be our significant advantage.

For example, of all the combat forces in the world today, the USAF is still a quantum step ahead on their ability to “turn out the lights.” It is a demonstrated war tipping capability and not just asserted capabilities.

However, if the PRC makes a military move, a well-designed and executed Air/Sea/Land Battle U.S. battle plan leveraging presence, scalability and multiple access can make such an attack become the PLA’s equivalent of the US WWII Battle of the Bulge.

The “Fighting Navy” is fully capable of executing a combat engagement strategy –“if it floats it sinks.”

Now, with the ever increasing lethality of anti-ship missiles, especially potential hyper-sonic cruise missiles, if the PLA establishes themselves on Taiwan, and has time to dig in, and modernize to their version of “no platform fights alone” it will position the expanded PRC position in the Pacific.

A PRC dominated Taiwan would be militarily poised to disrupt U.S. and allied operations and significantly disrupt the ability to operate in the strategic quadrangle.

If the PLA (generic for all PRC military forces) is given time to dig in and build a robust redundant ISR network from survivable hardened ground facilities and dug in and hardened 2nd Arty missiles batteries, it would be a significant new combat challenge.

The PLA combing survivable ISR 100 plus miles off the China coast linked with sea-based platforms, PLAAF attack planes, and their satellites (if they are allowed to survive) can be very deadly at sea for USN.

With the PLA propensity for digging, they will literally dig in, and shape combat capabilities at the heart of the strategic quadrangle.

Taiwan’s geographic position negates the entire concept of the strategic quadrangle; ultimately this could be a combat show-stopper.

It is no wonder that the self-declared ADIZ was yet another round of the PRC trying to assert its reach and affecting Taiwan.

Losing Taiwan, especially as PLA weapons modernize, would be a significant challenge to any Pacific Air/Sea campaign battle plan. Island building deserves a proactive response – strengthen Taiwan’s defenses within an overall Pacific defense strategy. Make the pivot to the Pacific real.

One mitigating factor is culturally all indicators are that the PLA is still a “hub-spoke” top down military,” which is so 20th Century. Such con-ops can be deadly and get better but still beatable with U.S. Allied Air/Sea evolving technology and con-ops.

The challenge is simply the PLA military concept of “mass” (a lot of combat capability) and survivability if protected correctly.

The U.S. Army Role in Taiwanese Defense

One of the technological capabilities which could play a role in enhancing the defense of Taiwan and connecting it more effectively to Pacific defense is the question of missile defense., The US Army could play a key role in providing the kind of allied capabilities, which would bolster Taiwan’s ability to DEFEND itself.

How can the US Army play a core role in Taiwan defense?

The first is their making a huge contribution by proliferating their world class Air Defense Capability. Any country that requests U.S. Big Army support with Air Defense Artillery should be encouraged and engaged.

Rather than tax the USAF to fly other U..S Army units around the Pacific, by being positioned on Taiwan and sorting out the capability to provide for missile defense FROM Taiwan, the US Army working with Taiwan could shape innovative new approaches to DEFENSE.

With respect to other Army combat skills, their own Field Manual (FM-1) answers the question of their most appropriate role in the Pacific.

The FM “Army and the Profession of Arms” is introduced with a brilliant quote from the late T.R Fehrenbach:

Chapter 1:

The Army and the Profession of Arms

…[Y]ou may fly over a land forever; you may bomb it, atomize it, pulverize it and wipe it clean of life—but if you desire to defend it, protect it, and keep it for civilization, you must do this on the ground, the way the Roman legions did, by putting your young men into the mud.

T.R. Fehrenbach This Kind of War

Putting this into context, recently the Air Force Association published a very smart insightful look at modern Airpower, on the dynamic shift between airpower and land power:

Airpower has eclipsed land power as the primary means of destroying enemy forces.

http://www.airforcemag.com/MagazineArchive/Pages/2014/February 2014/0214reversal.aspx

Earlier, the Brits also paid US Airpower a huge complement in an official MOD report:

“In 2014 our adversaries – state and non-state – will know that to confront the US and its allies in a conventional, force-on-force fight will be to lose; as Professor Colin Gray has said, ‘If an enemy chooses, or has no practical alternative other than to wage warfare in a regular conventional way, US air power will defeat it long before US ground power comes into contact.’”

http://sldinfo.wpstage.net/evolving-allied-perspectives-2/

Both sources are exactly right except on one type of combat–fighting over island real estate in the Pacific.

Iwo Jima proved the limits of direct fire, Naval Battleship canons shooting point blank shells the weight of a VWs pulverized the Island to little effect. Perhaps different results today could be achieved by accurate air ordinance, and we do have much better “bunker busters.” To be fair US and Allied air against dug in Island defenses, especially over an island the size of Taiwan, is an unresolved ongoing work in progress.

The key of course would be to position oneself not have to fight that battle in the first place: in effect get there first.

One way to signal ROC strategic importance is post more US “Big Army” troops on rotation into Taiwan, rather than have their emerging “Pacific Pathways” plan spend resources trying to achieve relevance around the PacRim as currently reported and demonstrated in Korea.

Proliferating ADA throughout the Pacific Rim and rotating appropriate ground combat units on and off Taiwan is tactically and strategically relevant.

There is no reach here with regard to the strategic relevance of the US Army.

It is imperative, as expressed in the Army’s own FM-1 thinking, to engage with the one country in which they can actually make a difference other than ADA. Rotating units of Big Army on and off Taiwan is their ultimate test case for Pacific Pathways relevance.

A US Army Division (or less to start) rotating in and out of the ROC would be a huge signal to PLA and make a difference in the event of war.

More” Big Army” is not needed in Japan, Korea, Philippines, Singapore et al.: ADA Army is.

Advocating for Big Army to focus on defending Taiwan should be the core element of their Pacific Pathway.

Rotating significant Big Army Units on and off Taiwan legally falls under two major provisions of The Taiwan Relations Act.

The US Army is not an offensive fighting force in the Pacific, unless they advocate fighting a land war in China, which will not and should not ever happen. It is clearly a DEFENSIVE force.

Stationed on Taiwan the Army does not have the ability to maneuver to engage in combat off the Island. Rotating US Army units is purely a defensive signal and falls inside provisions of the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA).

The TRA clearly permits such actions:

“In furtherance of the policy set forth in section 3301 of this title, the United States will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.”

Defense Articles are weapon systems, which U.S. provide and also are allowed, are “services.”

Taking into account the recent courageous fighting skills honed by the US Army from over a decade of combat it would be important to share their insights and provide large unit combined arms training “services” for the ROC Army.

One simple example is the ROC just purchased Apache Helicopters and Army combat experienced pilots could provide realistic training services.

From an American strategic viewpoint, and a signal to all our Pacific Allies, rotating Army units meet the minimum standards of prudent strategic planning as expressed in this provision:

“To maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”

History has shown that the PRC loves to tunnel so why not reverse that skill and have the US Army “dig” in on Taiwan.

Like the Army in Germany during the Cold War such a move is a signal of US and Allied resolve. Unlike the cold war victorious U.S. Army in Germany it would be seen as a 100% defensive move.

If not the U.S. Army who will provide allied defense of Taiwan?

If not now when?

F-35Bs to Taiwan

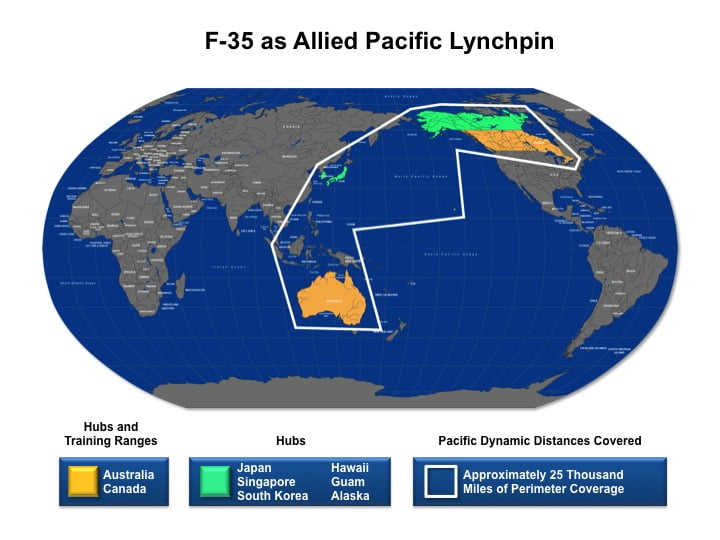

Another key initiative would be to provide F-35Bs and to leverage the evolving F-35 Pacific fleet – U.S., Australian, Japanese, South Korean and Singaporean.

By pure accident during a test flight over Pax River an F-35 system picked up a launch in Florida over 800 miles away. So the second a missile is launched against the fleet the Commander can light up the launch pad using a combination of B-2s and F-22s, especially in a their emerging Suppression of Enemy Air Defensive (SEAD) role along with at sea and sub launched cruise missiles.

Eventually UAS systems with combat firepower guided by F-35s and the robot revolution can take out any threat, launch be seen and die. This F-35 ability has been further validated in the exercise “Northern Edge.” It was reported one F-35 capable test bed aircraft using F-35 current sensor/radar systems could sweep over 50,000 square miles of ocean.

Too often analysts forget that as competitors like China innovate, so does the United States and its allies. But strikingly in conversations in the United States, the F-35 is the forgotten piece of the puzzle, although it can be central to the shaping of distributed operations.

In a war at sea, hitting the carrier’s flight deck can cripple the Carrier Battle Group (CBG) and thus get a mission kill on the both the Carrier and perhaps even the entire airborne air wing if they cannot successfully divert to a land base.

With no place to land, on the sea or land and with tanker fuel running low, assuming tankers can get airborne, the practical result will be the loss of extremely valuable air assets.

In such circumstances, The TacAir aircraft mortality rate would be the same as if it was during a combat engagement with either air-to-air or a ground –to-air weapons taking out the aircraft.

The only variable left, between simply flaming out in peacetime, vice the enemy getting a kinetic hit would be potential pilot survivability to fly and fight another day.

However, with declining inventories and limited industrial base left in U.S. to surge aircraft production a runway kill could mean the loss of air superiority and thus be a battle-tipping event, on land or sea.

Now something entirely new and revolutionary can be added to an Air Force, the VSTOL F-35B.

Traditionally the VSTOL concept, as personified by the remarkable AV-8, Harrier was only for ground attack. To be fair the RAF needed to use the AV-8 in their successful Falklands campaign as an air defense fighter because it was all they had.

The Harrier is not up to a fight against any advanced 4th gen. aircraft—let alone F-22 5th Gen. Fighters that have been designed for winning the air combat maneuvering fight (ACM) with advanced radar’s and missiles.

Now though, for the first time in history the same aircraft the F-35 can be successful in a multi-role.

The F-35, A, B &C type, model, series, all have the same revolutionary cockpit-the C5ISD-D “Fusion combat system” which also includes fleet wide “tron” warfare capabilities.

There has been a lot written about the F-35B not being as capable as the other non-VSTOL versions such as the land based F-35A and the Large carrier Battle Group (CBG) F-35, the USN F-35C.

The principle criticism is about the more limited range of the F-35B. In fact, the combat history of the VSTOL AV-8 shows that if properly deployed on land or sea the VSTOL capability is actually a significant range bonus. The Falklands war, and recent USN/USMC rescue of a Air Force pilot in the Libyan campaign proved that.

The other key point is limited payload in the vertical mode. Here again is where the F-35 T/M/S series have parity if the F-35B can make a long field take off or a rolling take off from a smaller aircraft carrier-with no traps nor cats needed it can carry it’s full weapons load-out.

Give all aircraft commanders the same set of strategic warning indicators of an attack because it would be a very weak air staff that would let their aircraft be killed on the ground or flight deck by a strategic surprise.

Consequently, the longer take off of the F-35 A, B or C with a full weapons complement makes no difference. Although history does show that tragically being surprised on the ground has happened.

Pearl Harbor is a very nasty example.

Of course, USN Carrier pilots during the “miracle at Midway” caught the Japanese Naval aircraft being serviced on their flight deck and returned the favor to turn the tide of the war in the pacific.

In addition to relying intelligence, and other early warning systems to alert an air force that an attack is coming so “do not get caught on the ground!” dispersal, revetments and bunkers can be designed to mitigate against a surprise attack.

Aircraft survivability on the ground is critical and a lot of effort has also gone into rapid runway repair skills and equipment to recover a strike package. All F-35 TMS have the same advantages with these types of precautions.

The strategic deterrence, with tactical flexibility, of the F-35B is in the recovery part of an air campaign when they return from a combat mission, especially if the enemy successfully attacks airfields.

Or is successful in hitting the carrier deck-they do not have to sink the Carrier to remove it from the fight just disable the deck. War is always a confused messy action reaction cycle, but the side with more options and the ability to remain combat enabled and dynamically flexible will have a significant advantage.

With ordinance expended, or not, the F-35B does not need a long runway to recover and this makes it a much more survivable platform — especially at sea where their might be no other place to go.

A call by the air battle commander-all runways are destroyed so find a long straight road and “good luck!” is a radio call no one should ever have to make.

In landing in the vertical mode the Marine test pilot in an F-35B, coming aboard the USS Wasp during sea trials put the nose gear in a one square box. So the unique vertical landing/recovery feature of landing anywhere will save the aircraft to fight another day.

It is much easier to get a fuel truck to an F-35B than build another A or C model, or land one of the numerous “decks” on other ships, even a T-AKE ship then ditch an F-35C at sea.

As Lt. General (Retired) Deptula has commented: “There is not a better place for utility of F-35B than in the defense of Taiwan.”

The ROC Air Force now includes less than 350 capable aircraft, the 87 F5E/F Tiger being outperformed by moderns’ Chinese aircraft. This includes Mirage 2000-5, F-16A/B and F-CK-1A/B Ching Kuo IDF. But, as result of the freeze of new sales by U.S., a “fighter gap” in favor of PRC has clearly happened. And a significant one affecting the ability to defend Taiwan.

It is time to shift the stage away from the “island building strategy” and provide concrete reminders to the PRC leadership that they are headed down the wrong path. They will find out now, in relative peacetime, or in a very worse situation.

Simply stating that peace is what you want, is not likely to make it so.

Simply standing aside and “interpreting” Chinese actions is frequently simply self-deterrence; not a prelude to thoughtful strategic action.

For a comprehensive look at a 21st century Pacific Defense strategy see the following:

For a PDF version of the article, see below:

A version of this article appears on the latest Second Line of Defense Forum which is focusing on the gathering storm.For a chance to comment on this article please go to the following: