U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, puts on gloves for his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

A U.S. Marine Corps cranial sits on the flight line at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, puts in ear protection for his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participates in his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, watches a CH-53E Super Stallion aircraft taxi on the flight line for his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participates in his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, walks to a CH-53E Super Stallion aircraft for his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, receives a gift after his final flight at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 2, 2024. The final flight commemorates an aviator's career accomplishments and is a tradition for pilots detaching from their units. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Brian Bullard)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, stand at attention during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Joshua M. Smith, a Medway, Maine native, the incoming commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, prays during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, march during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participate in a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines, assigned to 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing Band, perform during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participate in a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines, assigned to 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing Band, perform during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participate in a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, left, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, and Col. Joshua M. Smith, a Medway, Maine native, the incoming commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, receive the unit colors during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

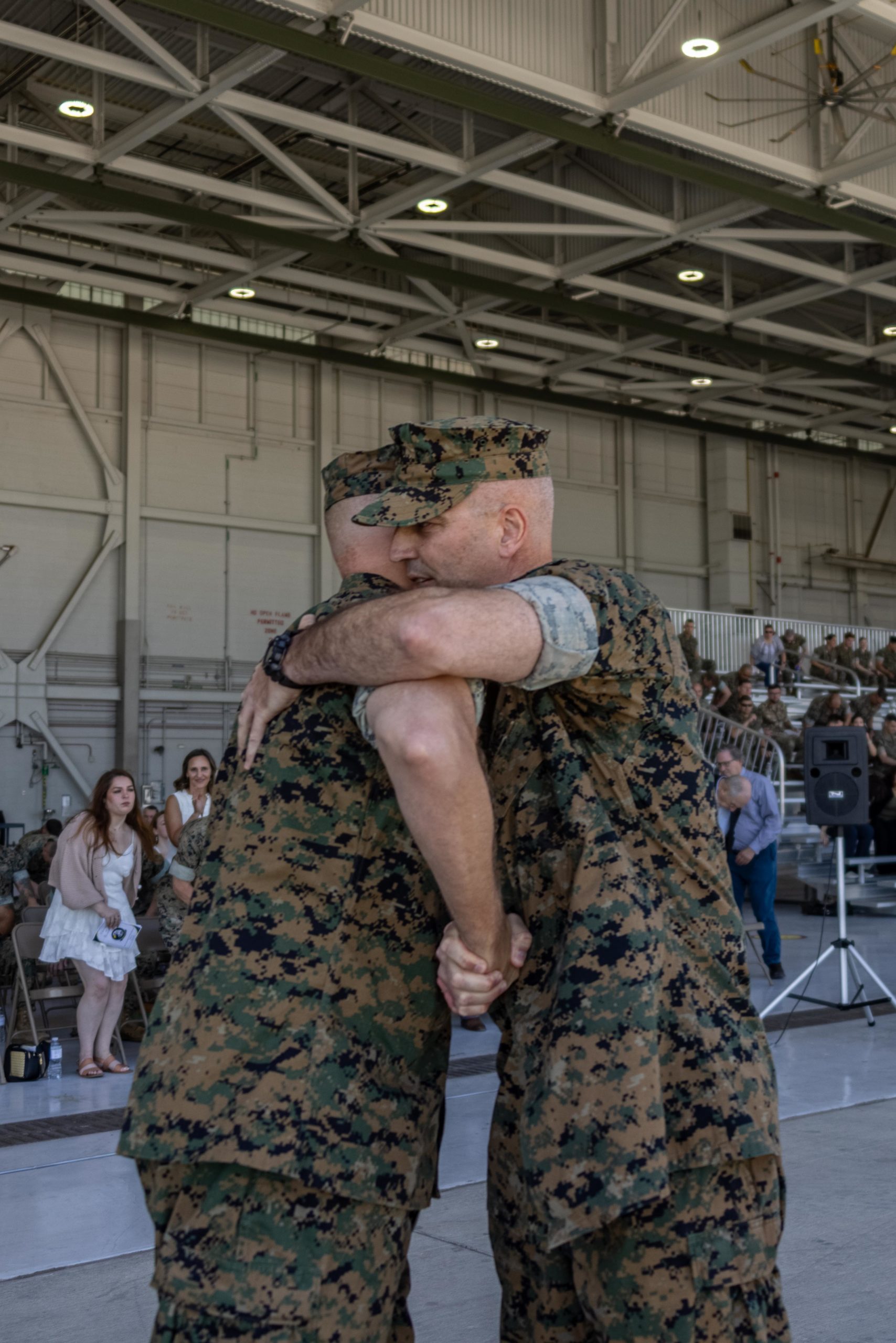

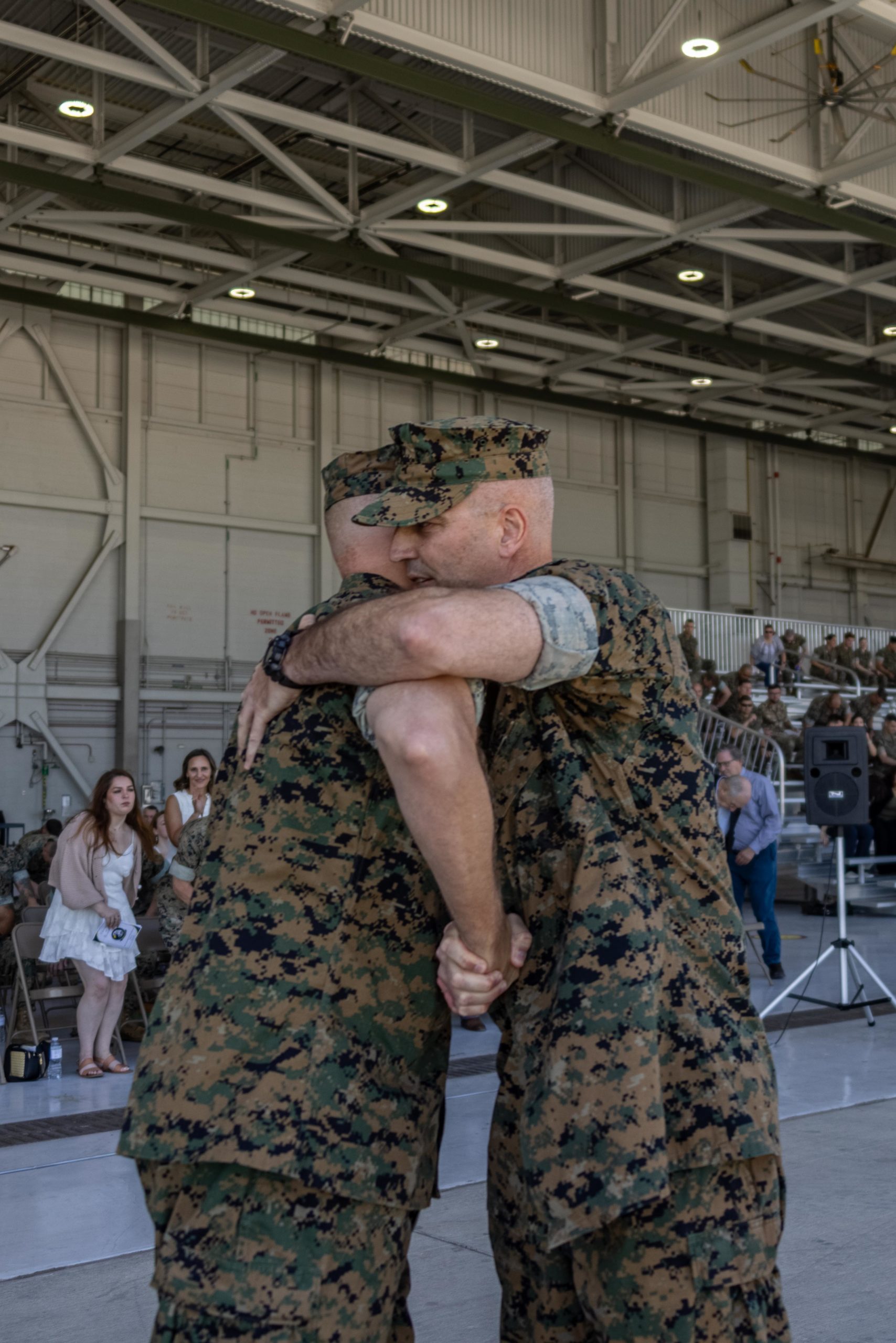

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, left, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, and Col. Joshua M. Smith, a Medway, Maine native, the incoming commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, share comradery during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, stands at attention during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participate in a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, salutes during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Joshua M. Smith, a Medway, Maine native, the incoming commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, salutes during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, stands at attention during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, left, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, is awarded by Maj. Gen. Thomas B. Savage, a Chico, California native, commanding general of Marine Air-Ground Task Force Training Command, Marine Corps Air-Ground Combat Center, during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Thomas B. Savage, a Chico, California native, commanding general of Marine Air-Ground Task Force Training Command, Marine Corps Air-Ground Combat Center, speaks during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps Col. Eric D. Purcell, a New Milford, Connecticut native, the outgoing commanding officer of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, speaks during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps, past and present commanding officers of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, stand at attention during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, salute during a pass and review as part of a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marines assigned to Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, participate in a pass and review during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)

U.S. Marine Corps, past and present commanding officers of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One, salute during a change of command ceremony at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, May 3, 2024. The MAWTS-1 Change of Command Ceremony marked the official passing of authority from the outgoing commanding officer, Col. Eric D. Purcell to the incoming commanding officer, Col. Joshua M. Smith. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Alejandro Fernandez)