02/14/2012 – In support of greater integration within the former Soviet Union, Kazakhstan has supported several initiatives: the Eurasian Economic Community, the Russia-Belarus-Kazakhstan Customs Union, and most recently a Eurasian Union, which would expand the Customs Union geographically and functionally, which was proposed by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin last year when he announced his presidential campaign plan.

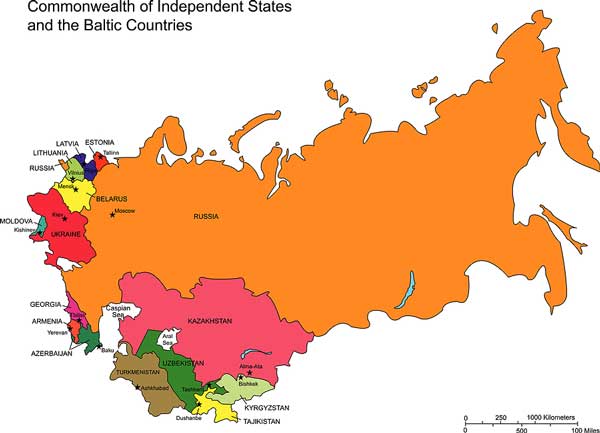

Many indications make evident the failure of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) to make much progress in promoting economic integration within the former Soviet space.

Not only are transportation networks lagging between CIS countries, but the members do not consistently coordinate their transportation development initiatives with one another, which prevents them from recreating the integrated transportation network that existed during the Soviet era.

One reason for the limited reciprocal investment between CIS members is that the citizens or companies of one member country have limited and unreliable means to protect their property rights or investment in another. CIS-wide legislation is underdeveloped, technical regulations are inconsistent, and authoritative dispute-resolution mechanisms that are both effective and efficient are rare. The members do not have a CIS-wide currency, but many of their national currencies are not readily convertible with one another. National legislation and regulations use different terms and procedures, leading to confusion over which country’s definitions prevails.

The member governments still resort to domestic and export subsidies, domestic preferences for government procurements, as well as export and import restrictions (e.g., camouflaged as sanitary measures) that violate free trade principles. As a result, the members’ economic relations are often governed by dozens of separate bilateral arrangements rather than a more efficient single integrated agreement.

At Nazarbayev’s initiative, some of the former Soviet republics established a Eurasian Economic Community (EAEC or EurAsEC) on October 10, 2000 in an attempt to overcome some of these problems. Nazarbayev made his proposal after the CIS proved unable to make adequate progress in the pursuit of economic integration and the customs union then existing between Kazakhstan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan seemed equally ineffective. (The economic crisis experienced by Russia and Kazakhstan in the late 1990s led them to levy heavy tariffs on each other’s imports.).

In 2005, EurAsEC absorbed the Organization of Central Asian Cooperation, whose members included Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Besides Kazakhstan, the EurAsEC’s membership roster originally included Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan. Uzbekistan joined somewhat later, while Armenia, Moldova, and Ukraine had observer status. The full members accounted for approximately three-fourths of all foreign commercial transactions occurring among the CIS members.

Uzbekistan only became a full member of the EurAsEC in 2006. Uzbekistan had been deepening with the pro-Moscow bloc of former Soviet republics for several years before then.

This process accelerated after the May 2005 military crackdown at Andijan led to a rupture of relations between Uzbekistan and many Western governments. Whereas Western countries criticized and subsequently sanctioned the Uzbek government for employing excessive force against the demonstrators, Russian officials endorsed the Uzbekistan crackdown as a justifiable response to a foreign-inspired terrorist attack. Tashkent accused the United States and certain European governments of encouraging anti-incumbent “colored” revolutions in the former Soviet republics and required almost all NATO forces to stop using its military facilities.

The EurAsEC has sought to promote economic and trade ties among the core countries that formed a unified economic system during the Soviet period by reducing custom tariffs, taxes, duties, and other factors impeding economic exchanges among them. Its stated objectives include creating a free trade zone, a common system of external tariffs, coordinating members’ relations with the World Trade Organization (WTO) and other international economic organizations, promoting uniform transportation networks and a common energy market, harmonizing national education and legal systems, and advancing members’ social, economic, cultural, and scientific development and cooperation.

The participants have discussed more specific projects concerning hydropower, reducing transportation barriers among members, harmonizing their regulations for finances and services, and promoting social ties between members. As with CIS meetings, the most important dialogues at EurAsEC sessions typically occur on the sidelines during bilateral discussions between national leaders.

With its smaller number of members, all favorably disposed toward Moscow’s leadership, EurAsEC represented a logical alternative to the more unwieldy and contentious CIS. By proceeding independently of the other member countries, the member governments aimed to circumvent several of the major impediments to deeper economic integration among the former Soviet republics that had degraded CIS efforts.

The EurAsEC also strengthened ties with another Moscow-dominated regional institution, the Collective Security Treaty Organization CSTO, an intergovernmental military alliance between Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Since the CSTO contains the same members as EurAsEC, plus Armenia, their leaders often hold sessions of both organizations when they assemble at regional summits. Proposals to unify the two organizations periodically arose but were never acted on.

Kazakhstan has been a leading advocate of strengthening the EurAsEC.

At the EurAsEC summit of August 2006, Nazarbayev said he “was always ready to discuss questions concerning integration within the EEC framework.” In January 2006, Russia and Kazakhstan created a Eurasian Development Bank, with a subscribed capital base of $1.5 billion. Its purpose was to help finance infrastructure and development and private sector activities in Central Asia. Analysts believed it could become an important instrument in enhancing EurAsEC’s effectiveness.

In late 2007, Tair Mansurov, previously governor of North Kazakhstan region and a former Kazakh ambassador to Russia, replaced Grigory Rapota, from Belarus, who had served as as EurAsEC Secretary General since October 2001, almost for the entire history of the organziation. At a EurAsEC meeting in January 2008, Kazakhstani Prime Minister Karim Masimov proposed convening a major business forum in Astana to consider creating a Eurasian Economic Union as well as establishing a Eurasian scientific club and a Eurasian bank devoted to promoting new technologies.

One clear Kazakhstani priority has been to promote cooperative initiatives within EurAsEC to assess how to regulate Central Asia’s unevenly distributed water resources and exploit the region’s potential to generate hydroelectric power. During the Soviet period, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan would store excess water in winter and then release it in summer to the downstream countries of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. According to the Soviet economic plan, these latter countries would use the water to support agriculture and cotton harvesting, receiving fossil fuels in return for winter heating. The break-up of the USSR has made it easier for Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, despite complaints by the other three countries, to use more water for hydropower to generate electricity for their own uses.

The International Crisis Group (ICG) and other institutions have long warned that the continued lack of an effective region-wide mechanism for managing water supplies could engender further conflicts among Central Asian countries. For example, a May 2002 ICG report warns that, “Tensions over water and energy have contributed to a generally uneasy political climate in Central Asia. Not only do they tend to provoke hostile rhetoric, but they have also prompted suggestions that the countries are willing to defend their interests by force if necessary.”

Kazakhstani analysts worked with others within the EurAsEC framework proposed a general set of principles for regulating Eurasian water supplies for members’ consideration. These include determining a suitable fuel and energy balance for the countries, restoring Soviet principles of irrigation for downstream states, promoting joint investment in building power stations, removing barriers for electricity companies in a common market for member states, and establishing multinational regulatory bodies.

But the EurAsEC’s integration efforts soon also lost steam and failed to create effective multinational regulatory bodies. The members’ diverging status with respect to the World Trade Organization (WTO) was a major factor complicating integration initiatives. For example, Kyrgyzstan had entered the WTO as a full member in 1998, the Russian government negotiated half-heartedly for entry, and while Belarus showed little interest in joining. Given the difficulties that Belarus and Russia alone have had in negotiating a possible currency union, its members have lost enthusiasm for creating a EurAsEC currency union.

Although relations between Russia and Kazakhstan are traditionally close, Nazarbayev has made clear that he does not want to rely exclusively on the CIS, EurAsEC, or other Russian-dominated institutions to promote Eurasian regional integration. Within the EurAsEC, Russia enjoys a 40% share in the voting and financial rights, whereas Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Uzbekistan only have 15% each, while Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan control merely 7.5% each.

Differences between Putin and Nazarbayev were evident at the October 2007 session of the EurAsEC Intergovernmental Council in Dushanbe. At the summit, Nazarbayev expressed dissatisfaction with Moscow’s domination dominant role within the EurAsEC and other former Soviet institutions, which he argued should function very differently than during the Moscow-dominated Soviet period: “Of course Russia is the biggest economy and we cooperate smoothly. But although the special role of France and Germany is taken into account in the European Union, they cannot make decisions without smaller member states.” At this Dushanbe summit, Nazarbayev repeated his longstanding call for the creation of a union of Central Asian countries that would “allow the region of 50 million people to create a self-sufficient market using both economic and political means.”

Nonetheless, it was precisely at this summit that Nazarbayev, Putin, and President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus signed the documents establishing the legal foundation for the EurAsEC’s long-delayed trilateral customs and trade union.

In the end, only Kazakhstan, Belarus, and Russia decided to form the current Customs Union.

The official reason given for proceeding without the other three EurAsEC members–Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan—was that they had yet to establish a legal basis for participating. The Russian media, however, cited a source in the Kremlin as acknowledging that the other three EurAsEC members were excluded due to their low levels of economic development.

But the Customs Union has also not achieved as much as its founders hoped. Russia tried to use the success of the Customs Union as a magnet to attract more members. At its founding, Putin stated that the Customs Union would gradually accept new members. Tajikistan President Emomali Rakhmonov announced his government’s intention to join the Customs Union in the future.

But until now the Customs Union has remained a trilateral enterprise. The few countries involved made the Customs Union less useful in terms of realizing economic efficiencies. Furthermore, the relationship between Russia and Kazakhstan was always the strongest, while Russia-Belarus economic ties has marked by considerable conflict. For example, the governments of Belarus and Russia disagreed over energy prices and tariff policy. Other differences over taxation and currency issues have blocked decade-long plans to establish a Russia-Belarus Union State.

Featured Image: Credit Bigstock