2014-04-08 By Robbin Laird

I had a chance to talk with the US Marine Corps, Pacific (MARFORPAC) in late February 2014 about their major project of reshaping and repositioning their forces in the Pacific over the next decade.

It is clear that a distributed laydown is a key element of shaping the deterrence in depth strategy in the Pacific and a fundamental tissue in building out an effective partnership strategy and capability in the region. .

The distributed laydown started as a real estate move FROM Okinawa TO Guam but it clear that under the press of events and with the emergence of partnering opportunities the DL has become something quite different. It is about re-shaping and re-configuring the USMC presence within an overall strategy for the joint force and enabling coalition capabilities as well.

The distributed laydown fits the geography of the Pacific and the evolving partnership dynamics in the region. The Pacific is vast; with many nations and many islands. The expeditionary quality of the USMC – which is evolving under the impact of new aviation and amphibious capabilities – is an excellent fit for the island quality of the region.

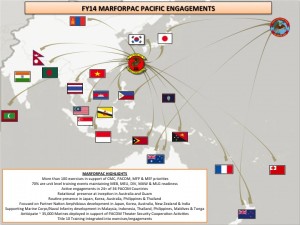

The USMC is building out four major areas to operate FROM (Japan, Guam, Hawaii and, on a rotational basis, Australia.) But as one member of the MARFORPAC staff put it: “We go from our basic locations TO a partner or area to train. We are mandated by the Congress to train our forces, and in practical terms in the Pacific, this means we move within the region to do so. And we are not training other nation’s forces; we train WITH other nation’s forces to shape congruent capabilities.”

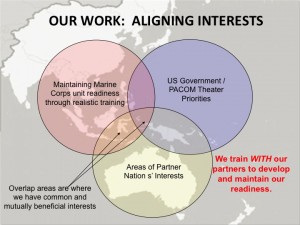

The basic template around which USMC training activities operate is at the intersection of three key dynamics: the required training for the USMC unit; meeting select PACOM Theater campaign priorities; and the partner nation’s focus or desires for the mutually training exercise or opportunity.

In effect, the training emerges from the sweet spot of the intersection of a Venn diagram of three cross cutting alignment of interests.

This template remains the same throughout the DL but it is implemented differently as an ability to operate from multiple locations, which allows the Marines to broaden their opportunities and shape more meaningful partnership opportunities.

The training regime is translated into a series of exercises executed throughout the year with partner forces. These exercises are central lynchpins in shaping effective working relationships in the region, which provide the foundation for any deterrence in depth strategy.

Nature abhors a vacuum and if you are not present you are absent. And by building out core working relationships, there is not a significant power void, which could otherwise be filled in by powers trying to reshape the rules of the game, and to perhaps impose a new order in the Pacific.

The USMC is a very cost effective force within the overall defense budget spending over all less than 10% of the defense budget.

2/3 of the USMC force is deployed to the Pacific. And in the Pacific the USMC spends $50 million per year on its exercises and of that 30% of the cost is for lift. It is clear that this touchstone for an ongoing commitment and deepening of partner working relationships needs to be fully supported and enhanced in the years to come and not be part of salami cutting approach to cutting defense expenditures.

Filling power vacuums by ongoing presence is a lot more effective than having to rush in later to deal with a crisis generated by collapse or someone else trying to force their will in the region.

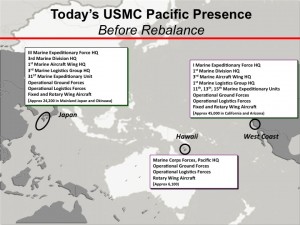

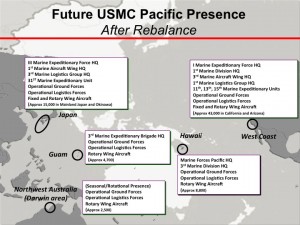

Another way to look at the DL is to compare the before and after of the process.

A key aspect of understanding the after is that it is a work in progress and is bound to change in the fluid decade ahead as needs become redefined and new partnership opportunities identified.

The Marines have been directed through International Agreements, spanning two different US administrations to execute force-positioning moves. This is political, but it’s not partisan.

The U.S. Secretary of Defense has mandated that at least 22,000 Marines in PACOM remain west of the International dateline in the distributed Marine Air Ground Task Force or MAGTF Laydown and he, congress, and the American people are not interested in a non-functional concept for a USMC force.

And, the Obama White House has directed the USMC to make to shift as well of forces from Okinawa to Guam and to a new working relationship with the Australians.

Beyond what is directed, the Marines need to maintain a ready-force in the face of existing training area encroachments, plus they have the requirement for training areas near the new force laydown locations

Within the distributed laydown, the Marines must retain the ability rapidly to respond to crises across the range of demands, from Major Combat operation in NE Asia to low-end Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) wherever it occurs.

Each location for the Marines is in transition as well. From Okinawa and Iwakuni, the Marines can locally train in Japan, Korea and the Philippines, as well as respond with “Fight Tonight” capabilities if necessary.

From Guam, the Marines can train locally in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) to the north, the Federated States of Micronesia to the south, and Palau and the Philippines to the west. Guam and CNMI provide the Marines something we do not have anywhere else in the Pacific: A location on U.S. soil where they can train unilaterally or with partner nations.

In broad terms, prior to the DL (ca. 2011), the Marines were located in Japan (25,000 in Mainland Japan and Okinawa), Hawaii (approximately 6,000) and on the West Coast (approximately 45,000 in California and Arizona). With the DL (ca. 2025), there will be a projected force distribution as follows: Mainland Japan and Okinawa (15,000), Guam (approximately 4700), Hawaii (approximately 8800), West Coast (approximately 43,000) and a rotational force in Northwest Australia of approximately 2500).

But this is clearly a work in progress.

What it is NOT is simply moving Marines from Okinawa to Guam. There are additive elements as well, mainly from USMC aviation assets as the USMC delivers new capabilities to the Pacific in the decade ahead.

The working relationship of the USMC-USN team in the Pacific is operating in a dynamic decade in which various partners are evolving their own amphibious or expeditionary capabilities as well.

The Australians and South Koreans are adding amphibious ships; the Japanese are extending the reach of their forces in the defense of Japan; and Singapore is adding F-35s and new tankers to extend its ability to defend the city-state.

The Marine Corps-USN team is obviously in the sweet spot to work these amphibious and expeditionary evolutions of core partners. There are several other partners working to expand their capacity to do littoral defense of their territory which in turn drive the desire to exercise and train with the USMC-USN team.

The equip side of train and equip forces for the USMC-USN team in the decade ahead during the DL is in flux as well. New capabilities are coming to the region which will are having or will have a significant effect on partnering opportunities and capabilities as well. And some items are under severe demand pressures and may well lead to the need to plus up targeting funding to meet these needs.

With regard to the new capabilities either in the region or coming the list is short but significant: the Osprey, the F-35B, the CH-53K, and the USS America.

The Osprey is rapidly becoming a lynchpin for connecting the forces moving in the DL. It is also an intriguing platform for some players in the region who are thinking about its acquisition as well for it fits the geography and needs in the region so well.

The F-35B is coming first to Japan and will operate throughout the region. The Singhs are buying F-35Bs, the Aussies and Japanese for sure F-35As, with the Japanese interested in Bs as well. The point is simple: The Marines are coming first to the region with the airplane and are the launch point for shaping perceptions and crafting working relationships with partners That are interested in expeditionary and amphibious-like capabilities.

Earlier this year, in a discussion with a USMC leader in the Pacific, the point about the insertion of the F-35 in a dynamic region was put this way:

“Viewed from Washington the US is either leading a process of allied defense or is facing off in a competition with China. Neither is the core dynamic. The reality is that multiple trends were happening at the same time which are creating a “steam roller out here.”

Among the trends cited were the following: South Korea shaping its expanded role in its own defense, the Japanese moving beyond a narrow concept of self defense and with the largest deployment outside of Japan since World War II seen in support of the Philippine relief effort, the Japanese are pushing outwards; the Aussies are shaping several innovations in defense and reaching out into the Pacific; the Filipinos are seeking more US presence within the islands.

While these trends are gaining momentum, the F-35 will be arriving into the region, which will “make it a focus point for discussions and efforts for coalition defense.”

The CH-53K is a less sexy addition to the USN-USMC team but expands significantly the ability to lift items off of ships and move them into play in the region as well as supporting more effectively the insertion of force in a MAGTF maneuver approach.

The coming of the USS America to San Diego and hopefully later to Guam is an important addition as well. It is a large amphibious ship able to support insertion of USMC forces through integration of unique and emerging expeditionary aviation capabilities such as the F-35B, CH-53K and the MV-22 more effectively than any current USN amphibious ship afloat today. The C2 will be better as well which make it a key element for supporting a MAGTF afloat.

And the potential interaction with the dynamic process of partnering going on in the region is significant as well.

During my discussions with the Australian Wedgetail squadron, we discussed the impact of the Wedgetail on their new LHD class and the potential impact which working with the USS America might have as well.

Another participant (in the roundtable with the Wedgetail squadron) noted that “because of the growth potential of the system in response to operational realities, we do not need to waste resources on redesigning the system prior to new capabilities showing up. We are a network management system so a key driver of the evolution will clearly be other assets emerging and then our working out with the new system our next code rewrite.”

A case in point is the coming of Aegis to the destroyer fleet and the new amphibious ships as well with their C2 systems.

And a coalition opportunity could well be the coming of the USS America, a new type of large deck amphib, to the Pacific later this year, which could provide an opportunity for cross learning as well.

With a significant shortfall in amphibious ships, the Marines have demonstrated a capacity to innovate as well.

One example is folding in the Joint High Speed Vessel into their need for movement of assets. As one participant in the MARFORPAC discussions put it: “It is clearly not an amphibious asset and can work in only some sea states. But given those facts, it can be very helpful in supporting assets as we move from our prime locations to exercise in some partner nations, and in supporting training over distance in Hawaii and Guam.”

Another example is how the Marines have leveraged the very capable Military Sealift Command ship the T-AKE. We have highlighted the capabilities of the T-AKE in several pieces on the website, but the Marines have recently demonstrated new ways to use the ship.

In an article in the Marine Corps Gazette, 2dLt Michael Wisotzky described how the Marines worked with the MSC and used the T-AKE as their seabase to support an exercise with a partner nation.

Every day for a week, my team was inserted into various locations by the ship’s organic helicopter detachment.

At the end of the day, the ship’s helicopters picked us up and returned us to the ship for overnight accommodations.

The next day we were off again. My team was fortunate enough to cross train with all of the participating nations, specifically, Brunei, Singapore and China.

Despite innovations, there are clear shortfalls as well, which need to be met however, and one of them is with regard to the KC-130Js.

These tanker-lift assets are in growing demand. The pairing with the Ospreys makes them an ideal presence, engagement and force insertion package. The emergence of a national demand for Special Purpose MAGTFs, which are built around this pairing, is another demand driver.

And the support for a widening circle of partner engagements is yet another. And the USAF with its own focus on supporting a dispersed force of USAF fighters is placing increasing reliance on using its C-17s in this key role as well. Which means that C-17s are not in surplus to meet USMC lift needs.

Another key aspect of the DL is shaping new capabilities for training. Training ranges are in short supply in the Pacific. The USMC is looking to modernize and expand their possibilities for training in Hawaii, Guam and the Marianas. Part of the need is driven by the longer-range operations facilitated by the Osprey and the coming of the F-35B. Changing con-ops to fit the 21st century is to support this century’s Marine Corps not the last.

And the evolving relationship with Australia offers possibilities as well.

Any critics of the USMC coming engagement in Australia have largely missed the point of the benefit to Australian forces of working with the USMC.This benefit can be seen on two levels.

First, the Guam and Marianas Joint Training facilities offer unique opportunities for the training of Aussie forces in the period ahead, and for the Marines training in Australia as well.

Second is that USMC-USN modernization hits a sweet spot with Aussie modernization in several spots, including F-35s, LHDs, Aegis, digital integration and interoperability, etc.

A measure of hitting the sweet spot is that two senior USMC operators participated in a seminar on the 5th generation opportunity at a leading Australian defense foundation.

In and of itself, this event is a recognition of the opportunities inherent in the cross fertilization from USMC and Aussie defense innovations.

In short, the distributed laydown over the decade ahead is a foundational element in shaping a more effective deterrence in depth approach.

And one, which is inextricably intertwined in reshaping with US allies an effective Pacific, defense approach for the 21st century.

For additional articles on the subject of the USMC shift, exercises in the region, Aussie modernization and cross-cutting modernizations see the following:

https://sldinfo.com/the-marines-the-aussies-and-cross-cutting-modernizations/

https://sldinfo.com/the-allies-air-sea-battle-and-the-way-ahead-in-pacific-defense/

https://sldinfo.com/the-re-set-of-pacific-defense-australia-and-japan-weigh-in/

https://sldinfo.com/the-f-35-global-enterprise-viewed-from-down-under/

Editor’s Note: The information and inputs from the MARFORPAC staff and Lt. General Robling provided a significant update on the section on the USMC strategy in the Pacific to be found in our latest article published in Joint Forces Quarterly:

“Forging a 21st Century Military Strategy: Leveraging Challenges”

For a PDF version of this article see the following: