When I visited MARFORPAC in 2014, it was the beginning of what the Obama Administration called the “Pivot to the Pacific.”

But that really did not happen as the Russians seized Crimea, and the wars in the Middle East ramped up.

Those demand sets still weigh heavily on the U.S. military and its ability to generate forces for Pacific operations.

But the basic template for the Marines in the Pacific was already being shaped, namely, a distributed laydown, from which the Marines could operate with greater strategic depth than being in Hawaii and on the West Coast of the United States.

In a 2014 article I highlighted the basic template which was being put in place as follows:

The U.S. Marine Corps is in the throes of a significant shift in the Pacific in the disposition of its forces. Because two thirds of Marines are deployed to the Pacific, such a shift is a key event in shaping the Marine Corps stance in the decade ahead…. The demand to support distributed forces is rising and will require attention to be paid to the connectors, lifters and various support elements.

Part of that demand can be met as allies modernize their own support elements, such as Australia and Singapore adding new Airbus tankers which could be leveraged to support Marine Corps Ospreys as well as other aircraft.

Indeed, a key element of the distributed laydown of our forces in the Pacific is the fact that it is occurring as core allies in the region are reshaping and modernizing their forces as well as partners coming to the table who wish to work with and host USMC forces operating on a rotational basis with their forces. The military and political demands for the kind of forces that the Marines are developing also are what allies and partners want for their operations.

In turn, this drives up the importance of exercises in the Pacific with joint and coalition forces to shape new capabilities for the distributed force.

The distributed laydown, the evolution of the capabilities for distributed forces, the modernization of allied forces and the growing interest in a diversity of partners to work with the USMC are all part of shaping what might be called a deterrence-in-depth strategy to deal with the threats and challenges facing the United States and its allies in shaping a 21st-century approach to Pacific defense….

It is clear that as the distributed approach is shaped in the Pacific, the demand on support, connectors and lift is going to increase. There will be a need for Military Sealift Command ships and amphibious ships and to draw heavily on new ships like the T-AKE and USNS Montford Point (MLP-1).

The demand on airlift is significant, and it’s clear from developments in the Pacific and new approaches like Special Purpose MAGTFs that KC-130Js need to be plussed up.

LtGen Robling, the MARFORPAC commander, underscored the nature of the challenge: “The demand signal goes up every year while the cost of using the lift goes up every year as well. This has me very concerned.

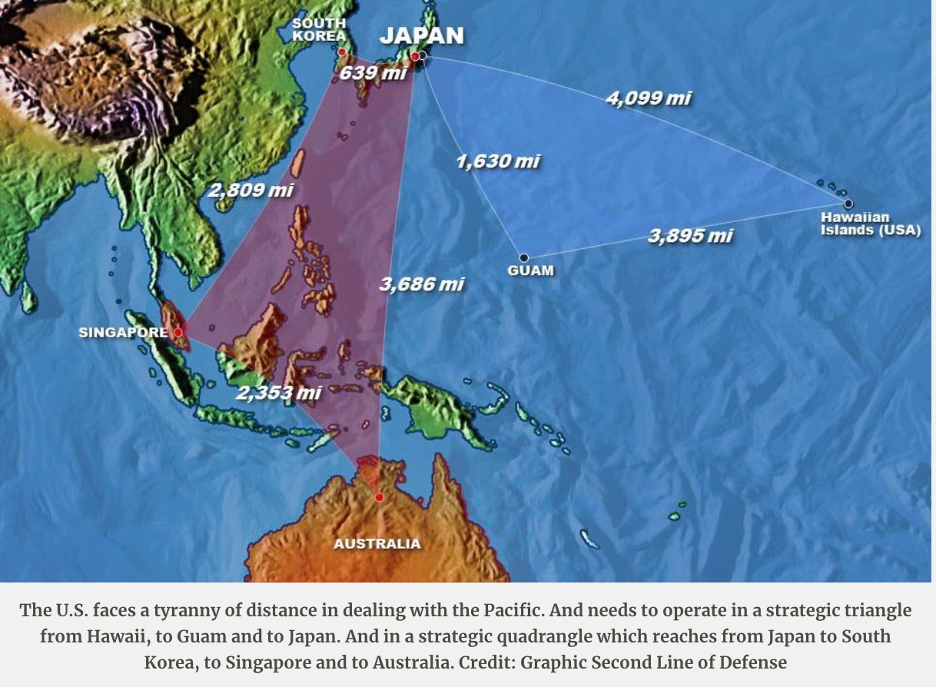

“The truth of the matter is the Asia Pacific region is 52 percent of the globe’s surface, and there are over 25,000 islands in the region. The distances and times necessary to respond to a crisis are significant. The size of the AOR [area of responsibility] is illustrated in part by the challenge of finding the missing Malaysian airliner.

“If you don’t have the inherent capability like the KC-130J aircraft to get your equipment and people into places rapidly, you can quickly become irrelevant. General Hawk Carlisle uses a term in his engagement strategy which is ‘places not bases.’

“America doesn’t want forward bases. This means you have to have the lift to get to places quickly, be able to operate in an expeditionary environment when you get there, and then leave when we are done.

Strengthening our current partnerships and making new ones will go a long way in helping us be successful at this strategy,” the general added. “We have to be invited in before we can help. If you don’t have prepositioned equipment already in these countries, then you have to move it in somehow.

“And, right now, we’re moving in either via naval shipping, black-bottom shipping, or when we really need it there quickly, via KC-130J aircraft or available C-17 aircraft. Right now, we are the only force in the Pacific that can get to a crisis quickly, and the only force that operates as an integrated air, sea and ground organization.”

Allies see the Marines clearly on the right path, and that path is a powerful one. But funding for the capabilities needed and the proper training will not happen by itself.

In my return to MARFORPAC in August 2021, the core template put in place in 2014 remains valid and a sound basis for moving ahead.

The major changes since then are clearly how both the Chinese and Russians are reaching out further into the Pacific, and the North Korean nuclear challenge has deepened.

During my MARFORPAC visit, I had a chance to be briefed by Joe Sampson, Director of Strategic Engagement, which provided an opportunity to talk about what has changed and what has not.

In this article I am going to leverage what I learned both during the visit and from the Sampson briefing, to shape my judgements about what has changed and what not. To be clear, I am not holding Sampson responsible for my judgments, but thank him for his information and insights provided during that briefing.

The first major takeaway is that the push further out into the Pacific by the Chinese and the Chinese military build out and engagements in the Pacific require the Marines to operate forward of their basing in the United States and in Hawaii.

One way to do so is to work on more effective operational capabilities to project force from three trajectories for operations in the Pacific.

The first is from Okinawa which is in the first island chain, and where the F-35s of the Marines provide a key element for projecting power.

The second is from the rebuild of Guam with the Marines having a base from which to rotate forces for operations.

The third is working with the Australian Defence Force from the Northern territories.

When I first visited MARFORPAC, the F-35 was not yet there; and the Marine Rotational Force-Darwin was just in its infancy. Both of these additions highlight how the Marines are working their approaches to operating in the Pacific.

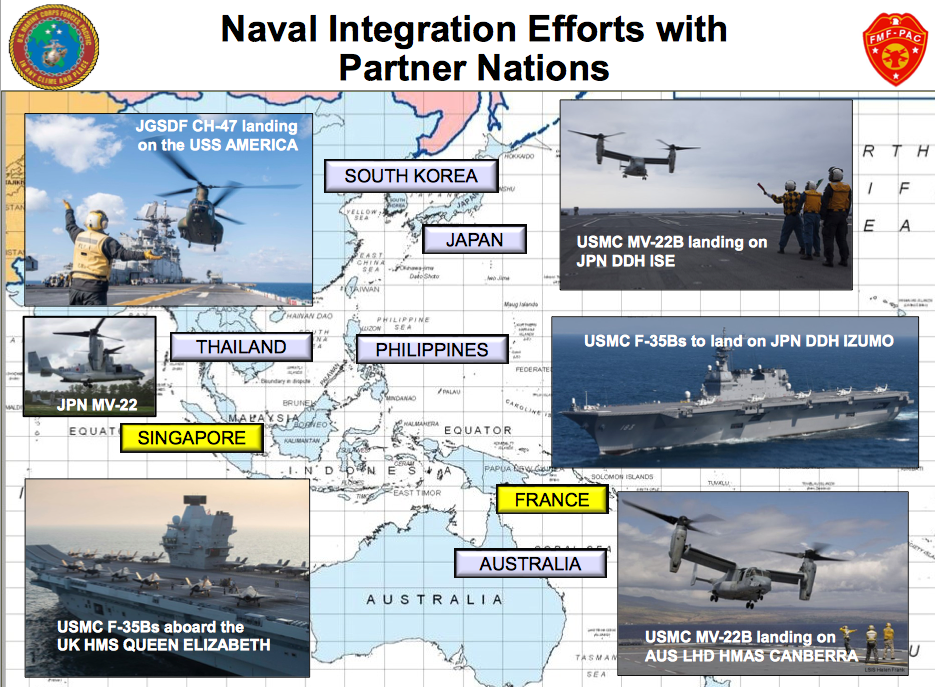

The F-35 allows the Marines to work closely with allies in the region who also have F-35s, prepare to operate with the South Koreans and Japanese who will operate F-35Bs as well off of their amphibious ships, and to integrate closely with the USAF as well.

The Australian working relationship is a key one, and having spent many years working with the Australians, the key impact will come as the Australians rework their military strategy in the region, and the Marines sort through how to most effectively work the Australians as they do so.

But the core takeaway is simply the importance of being able to project force from multiple trajectories.

The second major takeaway is the central role of training.

Training is a weapon system. But shaping a USMC trained properly for Pacific operations is challenging, as there is no one place to do so. They operate off of Hawaii and multiple islands but are limited in what they can do in specific training situations. Bringing the whole capability together is crucial and difficult. For the U.S. Navy and the USAF, bringing the full spectrum of capabilities into the current training environment is virtually impossible, and I mean literally impossible in either a live or virtual setting. For the Marines to work through how to integrate more effectively with the Navy or USAF is a major challenge going forward.

Sampson underscored the importance of training from another perspective as well. It is crucial to train with partners and allies, not simply from the standpoint of bringing what the U.S. can do to an allied or partner training event. Rather, it is crucial to understand the approach of those partners and allies not only to military training but with regard to their tactical and inferentially their strategic purposes for national defense in the region.

A third takeaway is how really crucial aviation is for the USMC to operate in what is lovingly called the “tyranny of distance.”

The range and speed of the Osprey finds a significant strategic space in the Pacific and the Marines as the only tiltrotor/fifth generation force in the world need clearly to leverage those capabilities going forward.

A fourth takeaway is the enhanced importance on naval integration but the shortage of amphibious ships is certainly a barrier to getting full value from what is possible for the fleet as an integrated fighting force.

When I was at MARFORPAC in 2014, there was a growing emphasis on the importance of “amphibiosity.” This emphasis remains significant as the Marines are focused on how to influence naval operations from their seabases to their expeditionary bases.

Now partner and allied nations are clearly ramping up their amphibious capabilities which provides a significant operational set of opportunities for the Marines going forward.

And working naval integration is not limited to the U.S. Navy, of course.

Marines operating off of HMS Queen Elizabeth in the Pacific or landing on Japanese amphibious ships is also part of the broad scale integration with naval forces in the Pacific as is highlighted in the following slide from Sampson’s brief.

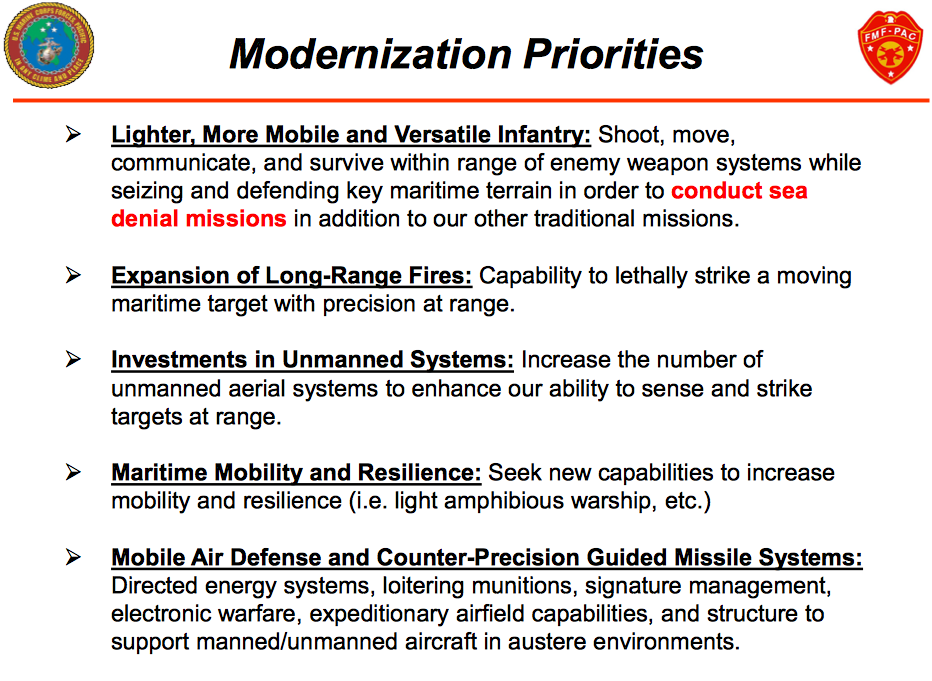

A fifth takeaway is the current USMC Commandant’s focus on leveraging expeditionary basing and redesigning the force to be more agile is a key part of MARFORC is currently working on.

Sampson provided a very helpful slide in his briefing which highlighted the modernization priorities which reflected the Commandant’s 2030 force design led effort.

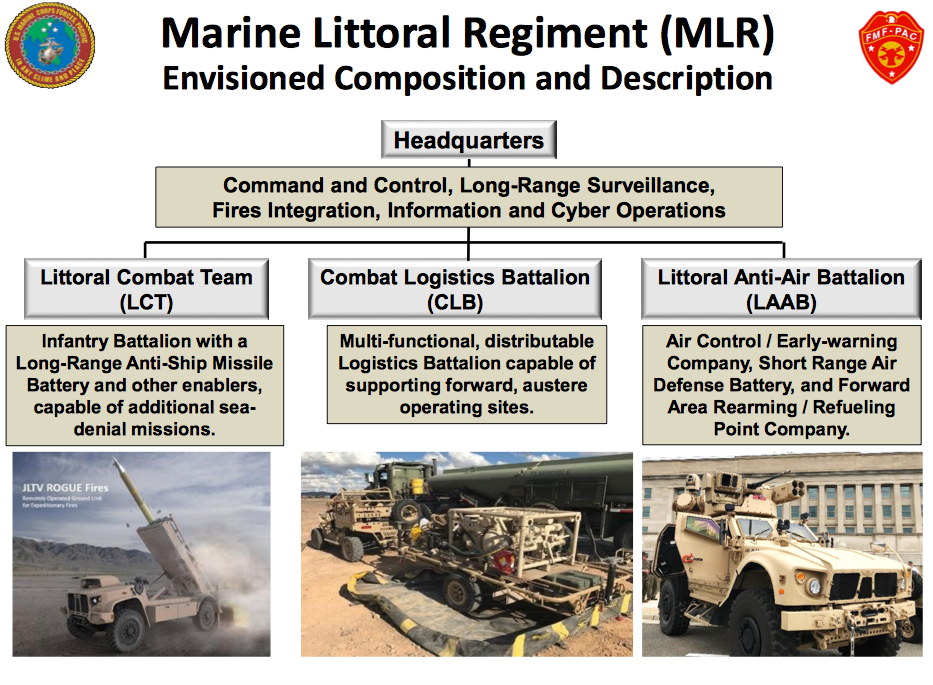

With regard to the “lighter, more mobile and versatile infantry” piece, a key effort is underway to shape a Marine Littoral Regiment, which was highlighted in the following slide from Sampson’s brief:

In short, the Marines are a key part of the effort to shape the kind of integrated distributed force crucial for full spectrum crisis management in the region.

They face several challenges in working the transition, which I will focus on in later articles.

Featured Photo: PHILIPPINE SEA (June 2, 2021) An MV-22B Osprey from the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit takes off from the flight deck of the forward-deployed amphibious assault ship USS America (LHA 6). America, lead ship of the America Amphibious Ready Group, is operating in the U.S. 7th Fleet area of operations to enhance interoperability with allies and partners and serve as a ready response force to defend peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Walter Estrada)