By Robbin Laird

On 30 April 2025, I had the chance to talk with Major White, the Operations Officer at VMGR-252. This is a KC-130J squadron based at the Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point and is part of 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing. The last time I visited the squadron was in 2014.

It must be remembered that 2nd MAW unlike the other two MAWs is not assigned to support a single geographic combatant command. It is co-located in North Carolina with II MEF but it is tasked as a global support force. This means that a squadron like the VMGR-252 truly has to be able to operate worldwide at a moment’s notice.

In the complex landscape of modern military operations, few platforms play as vital a role in Marine Corps aviation as the KC-130J. In the interview, Major White, an experienced KC-130J officer with multiple deployments and Weapons and Tactics Instructor (WTI) qualifications, revealed how this aircraft serves as the linchpin for Marine expeditionary capabilities worldwide.

“Our reach is unlimited,” Major White explains. “We can get there faster than pretty much anything else.” This self-deployable capability sets the KC-130J apart from other platforms that often require additional support to reach distant operational areas.

Dual-Role Platform: Air Refueling and Tactical Transport

What makes the KC-130J particularly valuable is its dual-role capability. The aircraft serves as both a critical air refueling platform and a tactical transport asset, though this creates inherent tensions in resource allocation.

The air refueling function is especially vital for CH-53 helicopters, which rely extensively on the KC-130J for refueling training and operations. “The 53s use us a lot because to my knowledge there’s no contract civilian tanker that can fly slow enough,” Major White explains. “We really work hard to make sure we’re able to sustain them.”

This tanking capability becomes increasingly important as the Marine Corps moves toward more distributed operations. The ability to extend the range of rotary-wing assets through aerial refueling directly enables the kind of distributed force posture envisioned in current Marine Corps doctrine.

Working with the CH-53K: A Window on the Way Ahead

The KC-130J squadron at Cherry Point is located nearby the new CH-53K squadron at New River, which enables them to experience working with the new generation heavy lift helicopter.

This is what the 2nd MAW said about what is pictured in the photo: “U.S. Marines with Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron (VMGR) 252 transfer supplies from a KC-130J Hercules into a CH-53K King Stallion assigned to Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron (HMH) 461 with an extended boom forklift – military millennium vehicle assigned to Marine Aviation Logistics Squadron (MALS) 29 at Marine Corps Air Station New River, North Carolina, June 7, 2023.

“The tail-to-tail transfer of supplies allowed distribution of sustainment in the minimum time period of vulnerability by reducing break-bulk requirements. U.S. Marines with 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW) experimented with dynamic, assault-support capabilities in a distributed-aviation environment. VMGR-252, HMH-461, and MALS-29 are subordinate units of 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing.”

This approach is facilitated by the new Kilo helicopter. The CH-53K‘s intermodal cargo system allows transfer of Air Mobility Command 463L pallets directly from fixed-wing transport aircraft (without the need for reconfiguration to wooden warehouse pallets) and lock them in place with an internal pallet locking system eliminating the need for the crisscrossing of cargo straps, significantly enhancing the speed of internal cargo operations and in-theater cargo throughput.

Meeting the Force Distribution Challenge

The distributed operations approach being prioritized by the services highlights the importance of such capabilities and more generally of a growing challenge facing the sustainment part of force deployment. If you distribute forces, for how long, where and how do you keep them supplied and their equipment operational?

Couplings like the KC-130J with the CH-53K go up in importance for sure. But there is a general problem of expanding the support for the support force, one might note. I feel particularly strongly that more funding for the sustainability of the fight tonight force needs to be made to enable higher readiness and sustainability rates going forward.

A significant portion of the interview focused on the often-overlooked aspect of military operations: logistics and sustainability. The distributed operations concept presents particular challenges for sustainment. The real question centers on how to sustain distributed forces.

Major White acknowledged the challenges of balancing the KC-130J’s dual roles: “There’s tension between the tanking function, which is important, and the lift function.” This becomes particularly critical when considering distributed operations, which “create an exponential increase in the problem of sustainability.”

Major White referenced the squadron’s work with HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System) rapid deployment, noting how they can quickly transport this critical weapon system over significant distances despite payload limitations.

Modernization Challenges

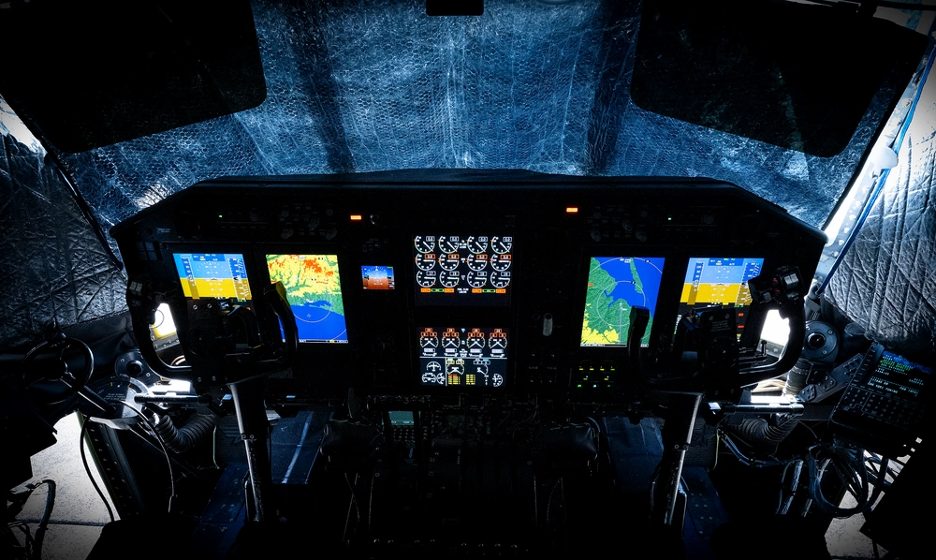

Like many platforms across the Marine Corps, the KC-130J faces modernization challenges. Major White highlighted that some of their aircraft are 15-20 years old with outdated software compared to Air Force equivalents. “We’ve bought a system, but the Air Force already upgraded to a better system, so we’re still behind where we could be,” he explained.

This points to a larger issue within defense acquisition: the focus on new platforms often overshadows the critical need to maintain and upgrade existing systems. As Major White notes, it’s not a flying problem but a supply problem.

Conclusion

Despite these challenges, Major White remains confident in the squadron’s ability to accomplish its mission. “We’re Marines, and we’ll find a way to get the mission done,” he stated, emphasizing how the integration of smart, creative personnel helps overcome resource limitations.

This integration is enhanced through the Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron (MAWTS) training cycles, which Major White described as crucial for cross-platform learning and innovation. “I think from every iteration, we learn from each other and make ourselves better.”

But as distributed operations become increasingly central to Marine Corps strategy, the question remains whether logistics and sustainability will receive the attention—and funding—they require.

In my personal view, if you’re going to force distribute, you’ve now created an exponential increase in the problem of sustainability, and unless you invest and think through how to deal with the new sustainability problem, the force won’t work as effectively as it could.

As Marine Corps operations continue to evolve toward more distributed concepts, the sustainment capabilities provided by platforms like the KC-130J will remain essential. Major White’s insights reveal both the impressive capabilities these aircraft bring to the fight and the ongoing challenges in keeping them ready for tomorrow’s conflicts.

In this context, the KC-130J stands as both a solution to current operational needs and a symbol of the broader challenges facing military logistics in an era of great power competition and distributed operations

Update on C-130 Modernization

This 2023 USAF article provided insight into the modernization path they are on with regard to their C-130s which is of relevance to the USMC as well.

The goal for the AMP Inc 2 modernization effort is supporting mobility air forces to sufficiently meet National Defense Strategy priorities, according to the C-130H legacy avionics branch. The upgrade provides a new flight management system, autopilot, large glass multifunctional displays, digital engine instruments, digital backbone and terrain awareness and warning system.

The 417th Flight Test Squadron’s aircrews were involved in the AMP upgrading since 2017 and began AMP Inc 2 developmental testing at Eglin in August on one aircraft with others to follow this month.

“This modification completely changes the interface for the crew to employ the C-130H,” said Maj. Jacob Duede, 417th FLTS experimental test pilot. “Aircrew essentially had to print the directions before flying and then type the information in using latitude and longitude or use ground-based navigation aids. This new mod is the newest GPS navigation with a by name search function and autopilot, all built into the aircraft.”

The built-in flight plan modification ability is particularly impactful for the pilots. Prior to AMP, to modify the flight plan, pilots coordinated with air traffic control, then looked up new coordinates in latitude and longitude with equipment brought onto the aircraft like a tablet or laptop. Then, the pilots took those numbers and entered them into the aircraft to adjust the flight plan.

“Depending on the proficiency of the crew, this could take 30-45 seconds or two to three minutes,” Duede said. “Either of which is a long time when in the air moving at four miles per minute.”

Using the new built-in multifunctional displays, the pilot can complete the entire process with a hand controller in less than 30 seconds.

“The new process is as quick as the first step of the old process. You just identify the point on the moving map, grab it and execute the flight plan,” said the major, a 10-year C-130 pilot.

Another new key aircraft component is the Integrated Terrain Awareness and Warning System. It is a commercially-used ground and object avoidance tool, but significantly upgraded to react to Air Force tactical flying requirements. The ITAWS, combined with the latest flight navigational programs, are all now built into the aircraft and available on screens easily assessable to the pilot, co-pilot and navigator. Currently, operational C-130H aircrews carry on tablets or laptops to access any navigational software.

All but three of the aircraft’s original analog gauges are gone to make way for the AMP system. In place of those gauges, that worked independently of each other, are six new brightly lit multifunctional displays working together throughout the aircraft’s flight deck.

“This is much larger than just a software or hardware upgrade,” said Duede. “It’s reconstructing and modernizing the aircraft’s entire cockpit area.”

The planning phase of the 417th FLTS’s developmental testing began in 2021 and continues at Eglin through the rest of the year.

During the DT flights, aircrew examine all aspects of these newly-installed tools, none of which existed within the aircraft before.

“This is an entirely new system,” said Caleb Reeves, 417th FLTS test engineer who helped design the test plan. “Everything we’re testing here is being done for the first time ever in this aircraft. We’re also examining if these untried systems perform in the ways we thought they would or not. That data allows us to adjust our testing and provide feedback to the manufacturer.”

The ITAWS test flights sometimes mean flying at terrain and at obstacles to check if those new warning systems react in the timely fashion and with the clarity.

Once the 96th Test Wing completes DT, the aircraft and mission shifts to Little Rock, Arkansas, where the Air National Guard/AFRC Test Center begins the operational test phase.

To better prepare them for OT and the upcoming aircraft changes, AATC pilots augment 417th FLTS aircrew roles during the current DT flying missions. This opportunity gives those aircrews a chance to see and learn the system early. This developmental seat-time helps guide the ANG and AFRC’s new technics, procedures, and training that becomes new aircraft standards for all operational units.

More than 23 Air Force Reserve and 54 Air National Guard C-130H aircraft will receive the AMP Inc 2 modification over the next 5 years at a cost of approximately $7 million per aircraft.

Featured image: U.S. Marines with Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM) 261 receive fuel in an MV-22B Osprey from a KC-130J Super Hercules with Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron (VMGR) 252 over the Atlantic Ocean near North Carolina, May 6, 2025. Photo by Lance Cpl. Mya Seymour.