2015-10-29 By Robbin Laird

Shaping 21st century U.S. and allied air combat capabilities is a function of the intersection of a number cross-cutting dynamics:

- The reshaping function of fifth generation warfare,

- Selective and appropriate modernization of the most capable of non-fifth generation aircraft,

- The introduction of longer range kinetic and non-kinetic strike platforms,

- The reshaping of a dynamically integrated combat force and of C2 systems,

- And the evolution of the weapons/robotic systems enterprise.

Dynamic and interactive change is how the air combat system will be transformed over time to enhance the lethality and range of effects which airpower can deliver in a multi-mission, multi-tasking environment.

Shaping a new weapons revolution where weapons are enabled throughout the attack and defense enterprise and not simply resident for organic platform operations is a key element of the way ahead.

For example, the new software enabled Meteor missile can be fired by one aircraft and delivered to target by that aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target.

One key dynamic clearly is the interaction between the evolution of the manned aircraft and of missile systems, whereby the aircraft is modified to make better use of the expanded capabilities and range of “smart weapons” and the weapons change themselves to more effectively interact with the modifications of the aircraft as well.

A case in point is the modernization of the Eurofighter intersecting with the introduction of the next generation air combat missile, the Meteor.

The upgrades underway for the Eurofighter will see the introduction of a new radar, which has built into it a much better way to work with missiles which themselves can “think” and “operate” more effectively in a fluid, high speed battlespace.

It is the intersection of the two which creates the new combat effect – a combat air system in which the aircraft can work the relationship with the missile to enhance the probably of the kill of adversary systems and at greater distance.

The intersection of co-modernizations is the core dynamic; which makes it difficult to describe if only one side of the modernization process is considered in terms of the overall combat capability.

From the Missile Modernization Perspective: The Meteor Missile

The new Meteor missile developed by MBDA is now in production.

It is representative of a new generation of air combat missiles for a wide gamut of new air systems.

It is planned for the F-35, the Eurofighter Typhoon, the Rafale, the Gripen and other 21st century aircraft.

Some of the baseline capabilities of the missile are as follows:

METEOR is being developed to meet the requirements of six European nations (UK, Italy, Spain, Germany, Sweden and France) for a superior Beyond Visual Range (BVR) missile system with the operational capability to excel in all current and future combat scenarios;

This collaboration of six European nations provides access to technology and expertise from across Europe.

The range and performance of the Meteor and its ability to enable both old and new air systems moves air-to-air weapons into the next generation.

What is METEOR and what are its benefits?

- A fast and highly maneuverable Beyond Visual Range air-to-air weapon

- Very large No Escape Zone owing to the air-breathing ramjet – several times that of current MRAAMs – resulting in a long stand-off range and high kill probability to ensure air superiority and pilot survivability;

- Networked capability through data-link

- Guidance is provided by an active radar seeker benefiting from enhanced technologies drawn from MBDA’s advanced seeker programmes;

- Capable of engaging air targets autonomously by night or day, in all weather and in severe electronic warfare environments;

- Equipped with both a proximity and impact fuse to ensure total target destruction in all circumstances.

At the heart of the Meteor program is an integrated development team led by the prime contractor, MBDA.

The missile was developed to meet the operational requirements of 6 partner nations and for 3 very different combat aircraft, the Eurofighter Typhoon, the Rafale and the Gripen.

It is also compatible with the F-35 weapon bay and is planned for inclusion in the Block 4 upgrade package.

Frequently, a multi-national program is more of a problem than a solution.

In this case, the challenge of building for multiple aircraft and partners at the same time, has given the MBDA team a leg up on the 21st century.

To design and build the missile, a comprehensive model was developed; this incorporated the various aspects of a successful missile, ranging from aircraft characteristics, to radar system performances, and the various operational scenarios and operational approaches of the different aircraft and air forces.

This has meant that MBDA has forged a very robust model for development, which is then at the heart of the production of the missile itself. The missile is software upgradeable so that changes over time will be written into the code in the model and directly incorporated into production runs.

Software upgradeability is a game changer for 21st century systems not well understood or highlighted by analysts.

In the past, new products would be developed to replace older ones in a progressive but linear dynamic. But now, one builds a core product with software upgradeability built in, and as operational experience is gained, the code is rewritten to shape new capabilities over time.

Eventually, one runs out of processor power and BUS performance and needs to consider a new product, but with software upgradeability, the time when one needs to do this is moved significantly forward in time.

It also allows more rapid response to evolving threats.

As threats evolve, re-programming the missiles can shape new capabilities, in this case the Meteor missile. The current production missile is believed to be using well below the maximum processing power and bus capacity of the missile.

Significant upgradeability is built in from the beginning.

Another key aspect of the missile is it is designed from the beginning to be employed on and off-board. It can be fired by one aircraft and delivered to target by that aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target.

The enhanced range of Meteor over legacy AMRAAM is important; but even more so are its systems which create the no-escape zone targeting capability.

Here the speed of the missile upon moving in on the target and the capability of the missile with its onboard sensors and reach back to sensors on the combat fleet allow it to “think” its way to a maneuvering and EW protected target.

The missile is designed to be able to operate via a three-phase speed control system.

First, it accelerates to cruise speed, which is dependent on launch condition and target altitude. This initial speed is selected to optimize range and maximize interception with the life of the missile even when the target turns to tail.

The second phase is mid-course guidance speed control. In this phase, the missile can accelerate and maximize intercept speed.

And in the third phase, at the extreme of its range, final acceleration to the target is generated to overcome any last-ditch evasive maneuver. Non-air breathing missiles are unable to achieve this.

The aim is to maximize fuel into speed at target intercept but not before. This is necessary because the range to intercept is unknown for long-range shots at launch, which is really determined by future target maneuver behavior so that the missile needs to adjust to that target behavior.

There are a number of integrated systems aboard the Meteor missile, which allows the missile to operate in the manner described.

But the secure data link system is an element, which enhances the ability of the missile as an organic asset to move from fire and forget, to fire and think through how best to hit the target, and to do so with onboard systems enhanced by an ability to leverage the sensors in the surrounding blue battlespace.

In this sense, it can operate either autonomously or leverage assets in the battlespace to destroy high-speed, maneuvering, targets, which are using electronic warfare and other systems to try to protect themselves.

From the Aircraft Modernization Perspective: The Eurofighter Case

The Eurofighter is a clear player in shaping European and global air forces.

It has reached critical mass and will be modernized through its operational life to work with new air assets and to deal with the evolving threat environment.

The program currently has seven customers, 599 committed aircraft orders, 446 deliveries to date, more than 300,000 flying hours with 100,000 employees and more than 400 companies involved in the program.

This kind of critical mass provides a solid foundation for the evolution of the program.

The Eurofighter consortium has launched a series of capability enhancements as part of a Capability Roadmap, which is designed to increase the combat effectiveness of the fighter.

It has evolved from an air defense aircraft to a multi-mission aircraft, notably with the addition of new weapons to subsume Tornado functions and to incorporate a new AESA radar as well as cockpit and linkage improvements as well.

It is the modernization effort associated with the new AESA radar and cockpit integration issues, which interests us most here with regard to intersecting modernization.

Paul Smith, an experienced RAF Typhoon pilot, now with Eurofighter put it this way:

The new Captor-E radar allows for greater capability to see and operate within the battlespace.

It provides for flexible task management with multifunctional performance and simultaneous modes for air to air and air to surface.

It provides an electronic attack capability, which complements our current EW capability on the aircraft as well as ESM, or electronic support measures as well.

The new radar will be able to leverage very effectively the new Meteor missile with its two-way data link to expand the capability of the aircraft to operate against adversary aircraft at a distance and in complex combat situations.

The situational awareness delivered by the fusion of Captor and other sensors in combination with the larger no escape zone of the Meteor should give Typhoon a significant combat advantage.

Lars Joergensen of Eurofighter provided his perspective as well on the cross-cutting modernization impact of radar with missile modernization:

Our current mechanically scanned radar has proven very good for the air to air mission.

With the AESA you have much more flexibility, and part of that flexibility will be to work with weapons differently in particular as a data facilitator.

The first new weapon were this will become very clear is Meteor where the airplane will interact with the data link on the missile to identify and destroy targets in a fluid air combat space. Other weapons will follow.

Thanks to the Eurofighter’s large nose aperture, combined with the ability to move the AESA antenna, we will be able to fire, guide and communicate with weapons “over the shoulder” so to speak while flying away from the threat, thus significantly enlarging our attack envelope with missiles.

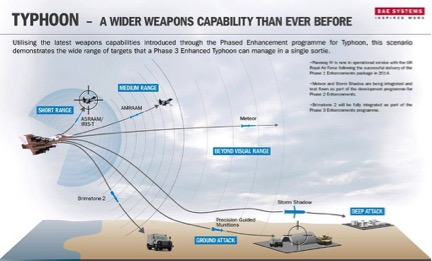

One of the key companies in the Eurofighter consortium BAES, has highlighted the missile upgrades to Eurofighter in the following graphic.

http://www.baesystems.com/en/feature/typhoon-king-of-swing-and-a-whole-lot-more

But what this graphic does not convey is how the Meteor missile/AESA combination lays a new foundation for the way ahead in terms of how the Eurofighter works with its missiles.

With the intersection of the new AESA radar on Eurofighter with the Meteor missile, a foundation has been laid to work a more interactive strike capability within the battlespace.

The radar with its independent modules and ability to track and see at distance interconnecting with the missile’s guidance system and data links can interactively “chase” the target until it is destroyed, a target at greater distance and operating with high maneuverability.

And moving from this foundation, the weapons enterprise intersecting with manned aircraft can operate quite differently as the missile can be fired from one platform and then “commanded” by another, which enhances not only the probability of kill but enhanced survivability of the air combat fleet.

It is part of moving from organic launch and “fire and forget” from a particular air platform, to launch from one platform and interactively hunting down the target but able to operate independently or tap into the “fleet” assets operating against the adversary.

Conclusion

The evolving air combat enterprise is undergoing significant change as interactive elements operating in combat packages enhance the effects which these force packages can provide.

This provides for a resilient package of honeycombed air assets which can operate by themselves but can be linked like lego blocks into a more expansive set of force capabilities.

This allows for shaping an enterprise, which can deliver the desired effects, but on the evolving electronic warfare battlefield.

Intersection among missiles, robotic systems (RPAs) and manned combat assets will form the core infrastructure moving forward.

Meteor being operated from F-35 as well as Eurofighter will allow better tactics for blue forces, with more efficient weapon deployment (fewer missiles fired = more targets engaged) against evolving air threats.

Editor’s Note: For earlier pieces related to this article, see the following:

https://sldinfo.com/what-do-the-eurofighter-and-f-35-have-in-common-the-meteor-missile/

https://sldinfo.com/italy-and-the-f-35-the-program-the-faco-and-the-coming-of-the-meteor-missile/

https://sldinfo.com/building-a-21st-century-weapon-the-case-of-the-meteor-missile/

https://sldinfo.com/meteor-missile-fired-successfully-from-eurofighter/

https://sldinfo.com/whitepapers/the-coming-of-the-meteor-missile/

https://sldinfo.com/expanding-the-effects-of-the-eurofighter-missile-modernization/

https://sldinfo.com/the-f-35-and-legacy-aircraft-re-norming-airpower-and-the-meteor-example/

https://sldinfo.com/the-weapons-enterprise-in-airpower-transition-the-royal-air-force-case/