08/02/2011 – The introduction of non-US stealth aircraft into the global competition is a significant development. The Chinese and Russians have introduced developmental prototypes that signify both capabilities and intentions to enter the stealth aircraft game. The former Secretary of Defense indicated that this competition was years away; but it has arrived today.

And make no mistake about it, an ability to introduce stealth into the battlespace changes the competition and the air battle management challenge. To quote one senior retired USAF officer: “If you don’t have a good communication and data link system among the blue 5th generation aircraft, they will not easily distinguish the nature of the adversaries own stealth airframe. The way to solve this is simply to have a honeycombed 5th generation fleet; but to not do this makes the bandit’s stealth platforms more effective in disrupting air battle management and mission success.”

The Russian T-50 comes as the culmination of a more mature aircraft development production process than does the Chinese. The T-50 exists and flies and will be available in the global fleet. And a senior Russian aerospace executive recently emphasized that he saw

good global sales prospects for the Sukhoi T-50 (PKA FA), including those in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and even a few African countries. The Russian Air Force will also continue to purchase these planes through at least the current SAP (2020), and probably beyond, while the Indian Air Force will begin buying the planes around 2015. He also believes that the Russian aircraft industry would further develop the Su-30/34/35 series, which he argued was completely different from the Su-27 sequence. He also stated that these 4th-generation planes would experience strong sales due to the Sukhoi’s commitment to produce 5th-generation craft. Buyers appreciate the company’s commitment to remain a leading developer of aerospace technology and could see how 5th-generation technology could be backfilled into their 4th-generation planes, as Sukhoi was doing in the Russian Air Force.

Flow down from the T-50 to earlier planes in the Russian export inventory as well as existing relationships and prospective relationships in South Korea are key considerations as well.

And an assessment of the aircraft by a key SLD team member has been as follows:

It is difficult to determine the actual capabilities of the PAK-FA T-50 because of conflicting information released by Sukhoi, Russian Air Force members, Putin, and other observers of this project. In addition, there is often a difference between desire and reality when it comes to Russian defense procurement. Russia must overcome several technical and performance obstacles in order for the Russian fighter to compete on a performance basis with the world’s pre-eminent fifth-generation fighter(s).

Despite claims by Russia’s NPO Saturn company, which leads the program to build new engines for the PAK FA, that the T-50 has flown its test flights with “completely new powerplants,” these statements are both unverified and seemingly contradicted by Russian government officials. The super-cruise engines intended for Russia’s fifth-generation fighters may not yet be available. Despite the development of Russian manufacturer NIIP of an active, electronically scanned array (AESA) radar system, similar to the system used by the F/A-22, for the PAK FA, it has not yet been seen on a test flight. This is a significant shortcoming in the development of the PAK FA as a modern stealth fighter, since stealth aircraft rely on their Low Probability of Intercept radar system for survival and their ability to “see and not be seen” gives such aircraft the ability to form a picture of their battlespace and gain air-to-air superiority.

It is unclear if the PAK FA can be completed in under 9 years. Historically, fourth- and fifth- generation fighters normally require 15 years or so to develop. The fact that the PAK FA has gone on several test flights without super-cruise engines or an LPI/AESA radar means that it is unlikely that the production goal of 1,000 operational ready PAK FAs will be ready by the stated 2015 date.

But funding and other support from the Indian government might help accelerate the timetable. India has become largest foreign customer for Russian military aircraft, and would be a logical buyer of this plane. In October 2007, Indian and Russian officials signed a preliminary agreement to collaborate in developing and manufacturing a 5th-generation fighter. The two governments are still negotiating a final contract. India’s Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL) wants to modify Sukhoi’s single-seat prototype into the twin-seat fighter.

The Chinese J-20 is a different case in play. The J-20 represents a step in the evolution of the Chinese aerospace industry as a whole. China is committed to developing modern civilian and military aerospace capabilities, which includes a significant moon effort.

The overall effort is significant and will clearly yield modern products. As the former chief scientist for the USAF has put it:

Quantity has a quality in and of itself. Again, I’ll often hear people say dismissively, “well yes, the Chinese are producing many more engineers, but they are not up to the standards that we have,” (although in many cases, they are). And to that I’ll answer “well, if we’re producing a thousand experts in our field, and they’re producing 10,000 experts in the field, and if 10-percent of their people are as good as the people we’re producing, they’re still doing pretty well.

If you generate a certain volume of expertise in a field; if you invest a certain amount in the field, not only in dollars, but also across the board in the workforce, you’re bound to see benefits.

We’ve seen the ability to leapfrog in technology. My friends in directed energy tell me that they have seen advances in the open literature in what the Chinese are doing that really surprised them, that they were moving at a pace that was much faster than anyone had previously expected. I think a lot of that is just putting in a lot of resources. We’ve done that in the past in our country, in the Manhattan project: when you think about the investment in the Manhattan project, we were able to realize incredible technological accomplishments with massive investments.

This significant commitment to technological development is being translated into growing capability for the Chinese Air Force. As retired Lt. General Deptula has underscored:

The ability of the Chinese to accelerate innovation in the air domain is quite impressive. They now have the ability to make major investments with the monies that are available from their economic growth for continued investment in research and development. That growth in the Chinese economy allows for investment in innovation. Unfortunately, until recently little concern has been evidenced by senior US defense leadership regarding the strategic challenges posed by the Chinese. How much investment is China making in advanced research and development vis-à-vis what the United States is doing? That will tell you how rapidly China will be able to accelerate in terms of military capability at a period in time where the United States is throttling back in terms of military capability.

A recent article in the Shanghai Daily stated that “CHINA is set to become the world’s most important center for innovation by 2020, overtaking both the United States and Japan…” That’s another piece that you hit on in the context of: “Look, this isn’t just about the military piece; there’s also another element with respect to aerospace.” The space piece is increasingly important as well. They’re becoming well aware of the importance of being able to dominate an air and space. “The shift is not because the US is doing less science and technology, but because countries like China and India are doing more research. China is now the second-largest producer of scientific papers after the US, and research and development spending by Asian nations in 2008 was US$387 billion, compared with US$384 billion in the US and US$280 billion in Europe.”

China used to view the United States as the gold standard for which to aspire to in terms of military capability to emulate. Now they’re specifically targeting how to disable or negate what used to be U.S. advantages. From their perspective it’s becoming increasingly easier and easier to do that as the current U.S. Department of Defense leadership has elected to focus on the present to a much greater degree than the future.

(For a briefing on Chinese air power see https://sldinfo.com/?p=14160)

The J-20 is part of the overall Chinese assertion into the global military competition. It is part of a strategy to expand Chinese exports and to shape perceptions of a significant upsurge in capability, which will confuse platforms with actual combat capability. Chinese propagandists are playing on the platform centric approach to the US and the West to shape perceptions by demonstrating a new platform. What they have not demonstrated is an ability to deploy actual combat capability. (https://sldinfo.com/?p=11421)

The underlying problem for the US and its allies is that US leadership for many reasons has frittered away a decade lead in 5th generation aircraft. Deptula highlighted one aspect of this problem: From their perspective it’s becoming increasingly easier and easier to do that as the current U.S. Department of Defense leadership has elected to focus on the present to a much greater degree than the future.

But the J-20 is part of a chain reaction.

The introduction of a new test aircraft by the PRC has caught the attention of many in Asia and the United States; as it clearly should. The new aircraft displaying stealth features, demonstrates if such a demonstration was need that the PRC is shaping new military capabilities for the period ahead. New unmanned aircraft, new missiles, a whole new approach to building civil and military aerospace capabilities, augmenting its Navy, expanding its commercial and global reach, building presence through counter-piracy, etc.

Although some may have been surprised, some were not.

One difficulty with U.S reactions has been to see this largely as a challenge to the United States. It is not. The Asian powers understand that this is part of the declared Chinese strategy to expand their presence and power throughout the Pacific and to shape an active export policy globally. The U.S. could stand in the way if it shapes effective capabilities in the decade ahead to play the crucial lynchpin role for allied forces in Asia to curtail Chinese ambitions. The Chinese clearly seek to shape the Pacific agenda, up to an including the Arctic.

Another difficulty is that the platform-centric approach dominates in viewing the development. If this is about an F-22 like aircraft, it is about F-22 like aircraft. It should be about the Chinese building significant capability across the board while the U.S. is engaged in Afghanistan : it is about continuing to build last generation aircraft and missiles, while delaying investments in today’s and tomorrow’s challenges which simply are not aligned with the Afghanitis strategy.

It is about continuing to build last generation aircraft and missiles, while delaying investments in today’s and tomorrow’s challenges which simply are not aligned with the Afghanitis strategy. (…) The Afghan engagement is eating up our military resources, which are no longer available to fund air and naval power transition.

Also, Chinese developments are not looked at by themselves, but are used by too many as a foil for their agendas. The anti-F22 community sees this new aircraft as simply a test aircraft, far from being an effective deployed asset. The transparency community sees this as a deviation from the true path the Chinese should follow, namely to be good bankers without military geopolitical aspirations. What this should be seen as is a manifestation of the tip of the spear of a comprehensive effort to shape a new capability in the Pacific to enhance Chinese influence and power, and to shape perceptions in Asia of a very different century, than the last half of the XXth century…..

The other aspects of the J-20 worthy of note is its impact on Chinese aspirations and capabilities to export arms. The capabilities which the Chinese are emphasizing – notably air and missile systems – are eminently exportable. By having a first class missile business a decade out, the Chinese can change regional power balances by export policy only incidentally supported by the power projection capability necessary to dominate in far away regions. The J-20 clearly helps in this effort. It is the Le Mans event, which helps the manufacturer to sell his show room product.

There is a significant global market for combat aircraft over the next 30 years globally. The Chinese have every intention of being the lead exporter in the second world; having the J-20 is a key driver for success in global export efforts.

The Chinese have every intention of being the lead exporter in the second world; having the J-20 is a key driver for success in global export efforts.

Another element of the global competition is the desire to respond to the Russian-Indian 5th generation aircraft. The strategic competition with India is significant for China, and they have little desire to see the Indians position themselves ahead of China in air and naval systems.

The J-20 is built on the top of the global shift in manufacturing capability towards China, a significant investment by China in global commodities and the enhanced presence of China on the world stage are all significant developments. When married to a growing investment in the development and fielding of military capabilities, something globally significant is afoot -of the sort which suggests changing epochs. (https://sldinfo.com/?p=14637)

What is clearly required is recognizing the centrality of the 5th generation opportunity for the US and its allies before it is frittered away by folks like Senator McCain who tweet rather than think.

The F-35 and the recovery of the F-22 into a re-norming of air power is really the key to meeting the 5th generation and evolving air combat or indeed combat challenges posed by the evolution of foreign capabilities. What is lost on most analysts is that the F-35 is not solely about air combat it is about combat.

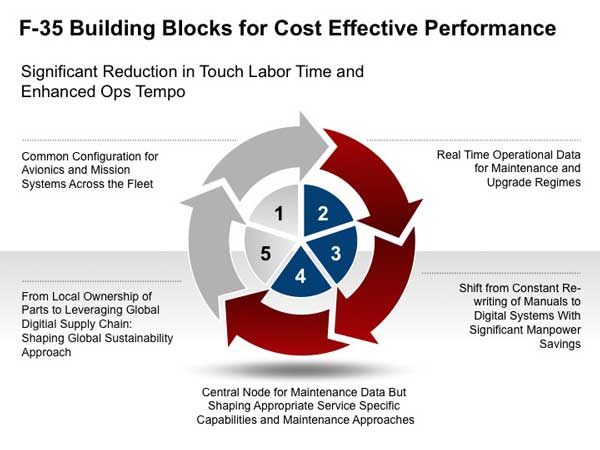

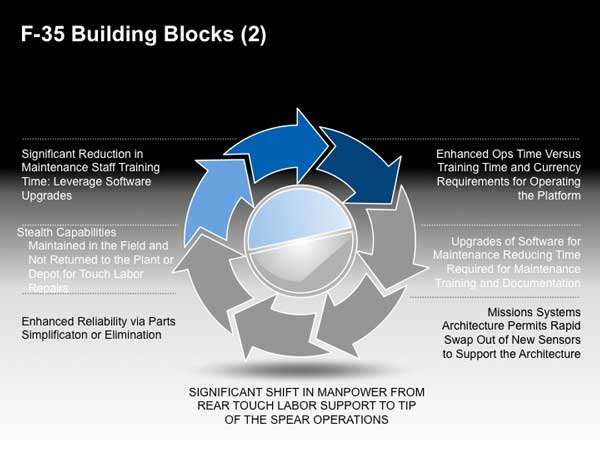

The F-35 is the first aircraft in history which can see 360 degrees around itself more than 800 miles and has integrated combat systems to manage that combat space. It is about a system not a platform. The F-35 as a combat system is about the central role of maintenance, upgrading, deployment readiness, development synergies provided by common software for upgrades and development. It is a system.

No service has understood this more clearly than the USMC. The F-35B is a fundamental glue that will allow the USMC and its MAGTF to operate across the spectrum of warfare and to transform how other assets function. It is a force for significant enhancement of combat efficiencies and effectiveness, rather than just being considered a day one aircraft enabled by stealth.

A senior member of the SLD team has provided a clear statement of the impact of the F-35B both on USN and USMC operations as well as overall joint combat capability:

In the not too distant future the US Navy/Marine and USAF team may have to establish presence from the sea in a potential combat theater. The threat will be great: friendly forces can be intermixed with opponents who will do whatever it takes to win. From placing IEDs, to employing small unit ambushes, to spotting for artillery and Multiple Launch Rockets, the enemy will be unforgiving and aggressive. In addition there is a large land Army with armor and land-based precision weapons nearby to attack.

The opposing forces also have an aviation component of Fighters and Attack Aircraft, along with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and some proficiency in offensive “cyber war” ready to engage. To make it even more difficult the enemy has located and identified potential airfields that could be occupied and has targeted them to be destroyed by terminally guided cruise and intermediate range ballistic missiles.

Finally, the fleet off shore is vulnerable to ship-killing missiles. The problem for US war planners is to secure a beachhead and build to victory from that beginning.

Traditionally, the “beachhead” was just that on a beach–but now it can be seizing territory inland first and attacking from the back door toward the sea to take a port and also grab an airfield.

The USAF flying high cover after being launched from bases far enough away to be safe from attack can establish Air Superiority, and the Navy Fighters can go on CAP (Combat Air Patrol) to protect the Fleet. Both services can launch offensive weapons from their fighters also from B-2s, surface ships and subs. UAVs can go into battle for ISR and offense “cyber” can be engaged. US “smart munitions” can attack enemy offensive rockets and missiles launch sites. There will be significant casualties on both sides.

But the Marines do the unexpected and land where the enemy does not have ease of access –a natural barrier perhaps, mountain range, water barrier, very open desert or even on the back side of urban sprawl—. Once established, logistical re-supply is a battle-tipping requirement.

Once ashore the one asset that can tip the battle and keep combat aviation engaged in conjunction with ground combat operations if runways are cratered is the F-35B, because every hard surface road is a landing strip and resupply can quickly arrive from Navy Amphibious ships by MV-22s and CH-53K.

The F-35B is a 5th Generation airborne stealth fighter with its own distributed intelligence center. Each aircraft has total 360-degree knowledge. If the enemy launches an attack from the air or ground, airborne sensors can instantaneously pick up the launch. The battle information displayed in each F-35B can be linked to UAV drivers as well as ground and airborne command centers to coordinate both offensive and defensive operations.

The sortie rate of the aircraft is more than just rearm and “gas and go”: it is continuity of operations with each aircraft linking in and out as they turn and burn—without losing situational awareness. This can all be done in locations that can come as a complete tactical surprise –the F-35B sortie rate action reaction cycle has an add dimension of unique and unexpected basing thus getting inside an opponent’s OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide and Act) loop.

Enemy air is predictable by needing a runway and consequently all the problems of precision weapons cratering their runways come into play for their battle plan—the F-35B does not have that vulnerability.

Now remove the USAF and USN Carrier Battle Group and instead of seeing USMC air and land forces engaged, it is only the Israeli Defense Force fighting for the survival of the free state of Israel. Israel is a nation surrounded by hostile forces. All of the threats mentioned above instead of being directed against US forces are life and death problems for Israeli defense planners. Consequently is there any surprise that the IAF is considering the F-35B. The Lightning II V/Stol version must be kept in production, because its combat potential is nowhere near fully understood and exploited.

It is a perfect aircraft for the Marines: think not only Israel, but other contingencies; think Korea or Taiwan in a major incident, or USMC being used to keep the promise with allies that trusted US. American Marines going back in from the sea to save an Iraqi town of innocents from being overrun or to stop the Taliban attacking a village is a debt that cannot be walked away from .

For the citizens of Israel, the IDF is fully capable of making informed and appropriate choices for their Nation’s survival. It is always up to them to do what they think best.

However, the F-35B maybe a perfect aircraft for their Combat situation as described above. If Israel has to fight for their very existence, the V/Stol capability may become invaluable — so why even debate not funding such a valuable resource for both the USMC and others — it can tip an entire war effort if employed successfully.

But for the synergies which the American and coalition F-35s can have on the evolution of combat capabilities, policy makers have to take it out of the platform ghetto. In the new approach to combat, no platform fights alone. And to quote that senior member of the SLD team:

Since all battlefield tactical technology is relative against a reactive enemy, a new 21st Century way to look at the American way of war is within our National Security grasp–technology, training, tactics and leadership can all come together if we have the political will.

The US military is developing and fielding weapons systems with the ability to fight to win, anywhere anytime. The future can only be seized by recognizing that 1, 2, 3, 4 “Generation” aviation discussions are platform linear. The concept of 5th Gen war and technology is “no platform fights alone.”

Consequently, “3 Dimensional” networked situational awareness warfare is the way ahead. This potential revolution, which can insure US military superiority for a generation is not understood with current platform debates that are stovepipes.