By Robbin Laird

On May 28, 2025, Michael Shoebridge, Director of Strategic Analysis Australia, and I travelled to Melbourne, Australia to visit C2 Robotics which is described on its website as follows:

“C2 Robotics specialises in the rapid development of cutting edge robotics and autonomous systems for Defence applications across the maritime, land and air domains. As a 100% Australian owned and operated company based in Melbourne, we work closely with local partners and suppliers to advance the sovereign capability of our nation.”

Our visit was hosted by the Chief Techonology Officer of C2 Robotics, Tom Loveard, and our colleague and friend Marcus Hellyer who is dual hatted as Head of Research at Strategic Analysis Australia and Strategic Advisor to C2 Robotics.

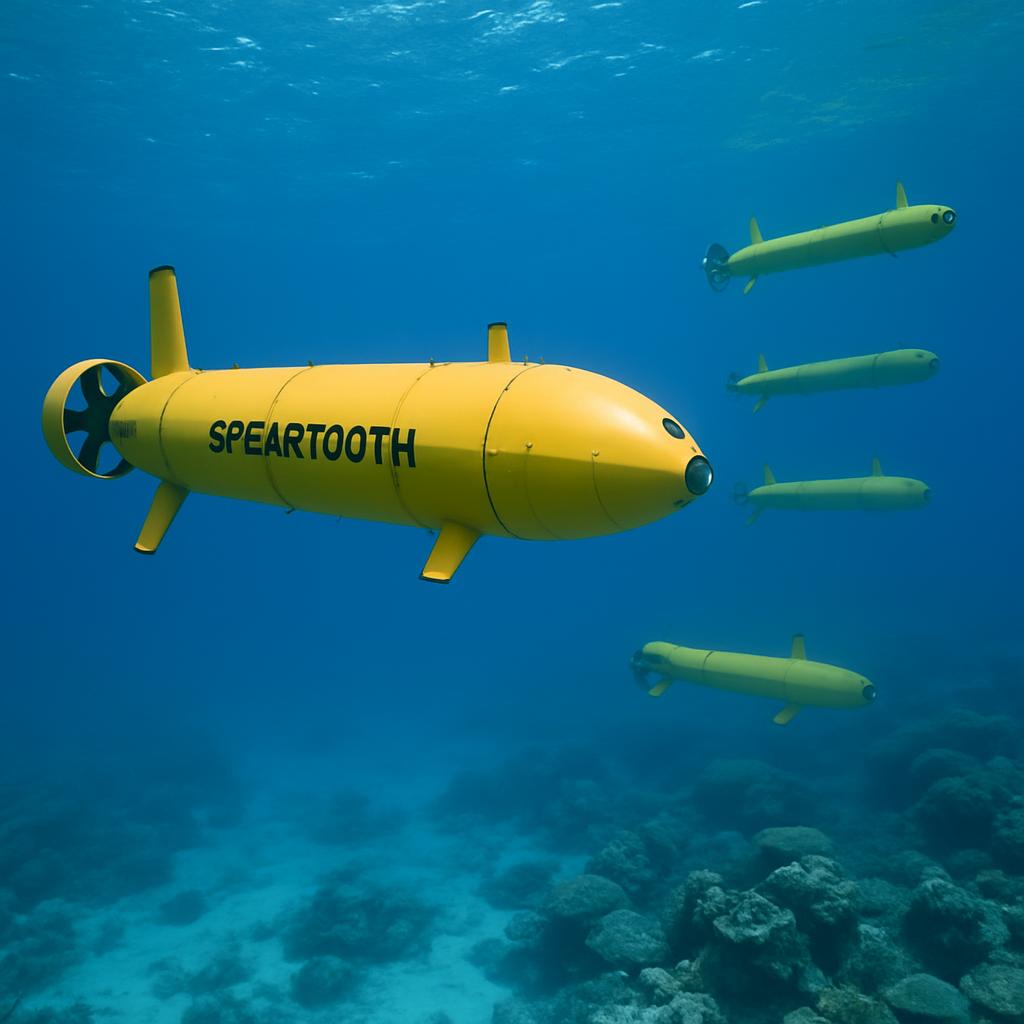

My own interest in going was to learn more about C2 Robotics Large Uncrewed Underwater Vessel (LUUV), the Speartooth. Last year I published a book on maritime autonomous systems and I just released my latest book on the subject entitled, A Paradigm Shift in Maritime Operations: Autonomous Systems and Their Impact.

The Speartooth is described on the C2 Robotics website as follows:

“Speartooth is a Large Uncrewed Underwater Vehicle (LUUV) designed for long range, long duration undersea operations. It brings a combination of highly advanced capabilities together with a modular, rapidly reconfigurable design specifically focused on manufacturing scalability and a revolutionary cost point that enables high volume production and deployment.”

There is much that can be said about the Speartooth about which we learned a great deal. But for me the most important question is how to understand what such capability represents. Usually, one sees a single photo of such a system and that completely misses the point – they operate as a network or a term I introduce into my latest book, a mesh fleet.

A Speartooth is not a submarine; it is a submersible platform which performs a task in concert with its mates. It can be deployed in terms which create a situation in which the adversary faces a large number of assets delivering a key effect and simply destroying some of these systems cannot shut down, say an ISR grid, if that is the payload which the Speartooth is deploying.

It is not so much to be understood to be attritable as it is about laying down a grid which remains operational even if some systems are lost and the overall capabilities are attenuated not eliminated. You lose a single submarine, and you can be out of business.

You lose a single Speartooth, and your capability is attenuated not eliminated. Moreover, by destroying a single Speartooth the adversary has revealed key information about themselves.

In a world where Ukrainian drones sink Russian warships and Houthi rebels challenge the U.S. Navy with asymmetric technologies, traditional defense thinking is rapidly becoming obsolete.

At the heart of this transformation is a fundamental shift in how we think about defense systems. Tom Loveard, CTO of C2 Robotics, explains that his company isn’t really building maritime platforms — they’re creating AI software capabilities that happen to manifest in products like their Speartooth autonomous underwater vehicle.

“We didn’t start building Speartooth as a maritime platforms company,” Loveard explains. “We started developing Speartooth as an asymmetric, agile engineering company with a very high focus on autonomy.”

This distinction matters because it represents a move away from the traditional model of building fixed platforms toward creating adaptable core capabilities that can evolve with rapidly changing technology.

The implications are profound. Whereas traditional defense systems lock militaries into specific configurations for decades, these new autonomous systems are designed for continuous adaptation. If a breakthrough in quantum navigation emerges tomorrow, it can be integrated into existing platforms within weeks rather than waiting for the next major upgrade cycle.

This technological shift comes at a crucial moment for Australian strategy. As Marcus Hellyer noted, there’s been a fundamental change in defense thinking: “If you’re an ADF that’s thinking about deploying to fight land wars against insurgents in the Middle East, there’s not a lot of space for autonomous systems. But if you are thinking about defending Australia against a major power adversary, you now have conceptual space for these systems.”

The numbers tell the story starkly. Even Australia’s most capable forces run into limitations quickly. Operating fighter aircraft with tankers and long-range missiles might reach 1,500-2,000 kilometers, but Australia has only seven tankers in service and 80 JASSM missiles on order. “That’s a couple of days usage,” Hellyer observes. “We just run out of scale, of mass, really quickly.”

This is where autonomous systems offer a different calculus. Instead of a few exquisite platforms costing billions, Australia could deploy a large number of autonomous vehicles that create persistent coverage of the northern approaches. It’s not about replacing submarines — it’s about creating a defensive network that complicates any adversary’s calculations about where and how to operate.

Perhaps most intriguingly, this approach could transform Australia’s defense industrial base. Unlike traditional defense manufacturing, which relies on specialized contractors and boutique production, C2 Robotics has designed Speartooth to leverage existing commercial supply chains.

“Much of the core manufacturing can be done by existing manufacturers that are already here today in Australia,” Loveard explains. “We’ve really chosen systems, technologies, and components that are highly available in commodity markets.” This means drawing on Australia’s automotive, oil and gas, mining, and agricultural sectors—industries that already exist and have scale.

The comparison to electric vehicles is revealing. “Speartooth actually has a lot of commonality” with modern electric cars, Loveard notes. “When you look at what’s in a current, modern-day car that you go and buy for anywhere from $20,000 to $100,000, the technology you get is actually very impressive.” The key difference is scale — those systems cost $50,000 per unit because they’re produced in huge volumes using broad industrial networks.

This manufacturing approach addresses what Loveard calls the “chicken and egg problem” in defense procurement. Traditionally, you start with expensive, exquisite platforms, which means the payloads and effects must also be expensive and highly specialized. Low numbers and high costs become self-reinforcing.

“Speartooth tries to break that chicken and egg problem by saying we want to provide essentially a marketplace for very low cost, high volume payloads and effects,” Loveard explains. By creating a delivery platform designed for mass production, it becomes economically viable to develop cheaper sensors and weapons systems.

The sustainment model is equally revolutionary. Unlike traditional platforms that operate continuously and require constant maintenance, autonomous systems operate more like munitions. “If you had 1,000 Speartooths, you’re not using all 1,000,” Hellyer notes. “Most of them are going to sit in a container. You just want to check them every now and then to make sure they’re ready to go.”

This technological shift also addresses Australia’s military recruitment challenges in unexpected ways. As Michael Shoebridge f observed, “If I was an 18-year-old kid coming out of high school, the last place I want to be is on a frigate or inside a tank, because all I’m doing is going on YouTube and seeing videos of Russian ships sinking, of tanks being destroyed by drones. I want to be a drone operator.”

The Australian Defense Force once recruited with the tagline “smart people, smart machines,” promising young people access to the world’s most exciting technology. But as Shoebridge points out, telling someone they might get a ride on a nuclear submarine in 20 years isn’t motivating. The two-to-four-year development cycles of autonomous systems offer something much more immediate and exciting.

Beyond immediate military capabilities, this approach offers Australia a path toward greater strategic independence. The conversation reveals deep concerns about Australia’s current trajectory which I characterized as too dependent on American defense while increasingly integrated into Chinese manufacturing supply chains.

I put it this way: Australia needs to “hug my American brother but build more independence for myself.” The autonomous systems approach accomplishes both goals —strengthening the alliance with the United States while reducing dependence on both American exquisite platforms and Chinese manufacturing.

The geopolitical context makes this urgent. As Hellyer noted, America’s military is smaller, more under-capitalized, and older than it’s been in decades. Even with increased defense spending, the structural problems won’t be easily resolved. Australia can’t assume American forces will always be available to fill capability gaps.

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine provides a real-time laboratory for these concepts. As Loveard observes, “The great revolutions from Ukraine have not just been technical revolutions. There have also been procurement revolutions and tactics and procedures revolutions.” The tight coupling between industry, procurement, and users has enabled rapid adaptation and innovation.

But the technology is spreading beyond major conflicts. “There was footage on the internet last week of rebels in Myanmar taking out a government helicopter with a quadcopter drone,” Hellyer notes. “If we somehow think that in the Indo-Pacific, we’re quarantined from what’s going on, we’re mistaken. Drug dealers and non-state actors are already adopting these technologies.

This democratization of advanced capabilities means Australia faces threats not just from major powers but from a range of smaller actors who can now access disruptive technologies. The Houthis’ impact on Red Sea shipping with relatively simple systems demonstrates how small actors can create strategic effects.

Our conversation underscored both the promise and the challenges of this transformation. The technology exists right now, the manufacturing pathways are clear, and the strategic logic is compelling. The main barriers are institutional and conceptual.

As Shoebridge suggests, the solution may not be to abandon existing programs like the Hunter frigates or AUKUS submarines, but to pursue parallel tracks. “Within the time frames that those programs are operating, you need this faster delivery,” he argues. The budgets required for mass autonomous systems are “pretty small by comparison to many of these other systems.”

The key is recognizing that the world has changed fundamentally. The comfortable assumptions of the post-Cold War era — American dominance, rules-based order, predictable threats — are breaking down. In this new environment, the ability to adapt quickly becomes more valuable than having the most exquisite platforms.

What emerges from this discussion is a vision of defense transformation that goes far beyond new weapons systems. It’s about creating an adaptive ecosystem that can evolve with changing technology and strategic circumstances.

This isn’t science fiction or distant future thinking — it’s happening now.

The autonomous revolution offers Australia a chance to achieve greater security, strategic independence, and industrial sovereignty simultaneously.

But it requires abandoning comfortable assumptions about how defense systems are developed, manufactured, and employed. In a world where the pace of change is accelerating, the biggest risk may be standing still.

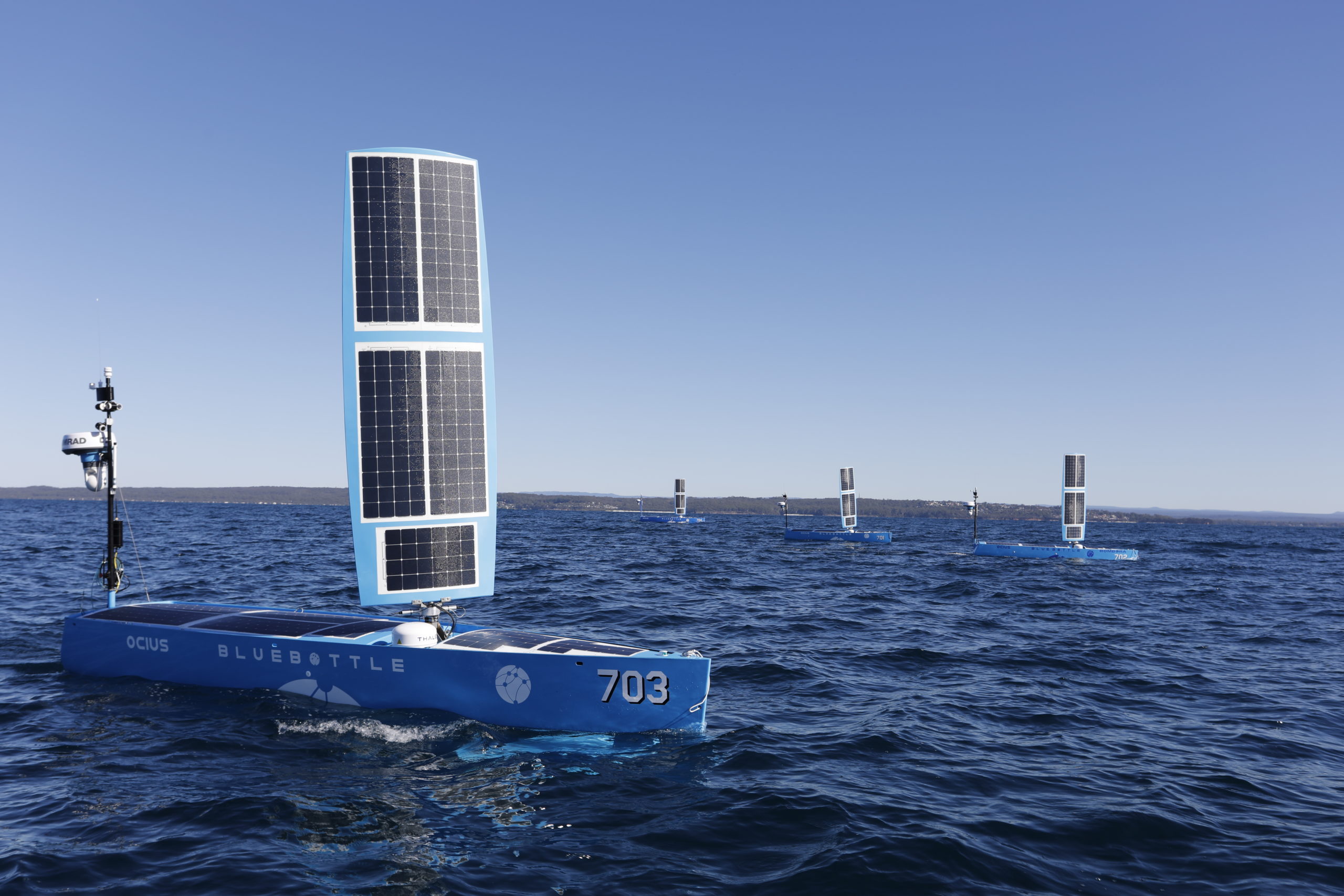

Featured photo: The Speartooth as seen in a C2 Robotics video

But for me, such capability is best understood in kill web or mesh fleet terms, so I generated an AI image of the Speartooth “fleet” being launched for deployment to create an ISR grid.

On the Amazon U.S. site:

On the Amazon Australian site: