By Robbin Laird

This year’s International Fighter Conference held in Berlin provided a chance for the participants and the attendees to focus on the role of fighters in what we have been calling the strategic shift, namely, the shift from the land wars to operating in higher intensity operations against peer competitors.

It is clear that combat capabilities and operations are being recrafted across the board with fighters at the center of that shift, and their evolution, of course, being affected as well as roles and operational contexts change.

The baseline assumption for the conference can be simply put: air superiority can no longer be assumed in operations but needs to be created in contested environments.

It is clear that competitors like China and Russia have put and are putting significant effort into shaping concepts of operations and force structure modernizations which will allow them to contest the ability of the liberal democracies to establish air superiority and to dominate future crises.

There was a clear consensus on this point, but, of course, working the specifics of how one would defeat such an adversary in an air campaign gets at broader and more specific force design and concepts of operations.

The conference worked from the common assumption rather than focusing on specific options.

But the way ahead was as contested in the presentations and discussions as any considerations for operations in contested airspace.

The assumption that the air forces of the liberal democracies faced a common threat of operating in contested airspace was not contested; but the preferred approaches or the approaches being followed were.

There are clearly different approaches being taken to this challenge and each approach deserves to be examined.

The clear force for change is the coming of the F-35 global enterprise.

As a senior RAF officer put it, “The future is now.”

He included in his presentation a slide outlining what from his point of view constituted the F-35 global enterprise and how the UK would both contribute to and benefit from that enterprise.

This slide laid out how he saw interactions among F-35 partners in shaping common and distinctive approaches to air power modernization driven by the introduction of the F-35.

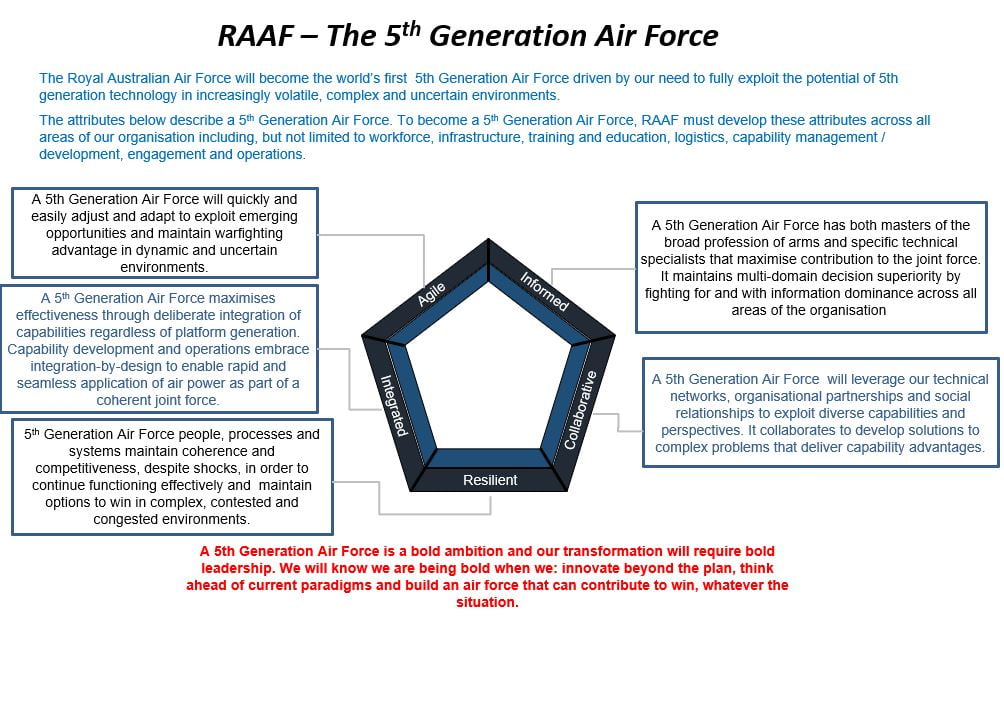

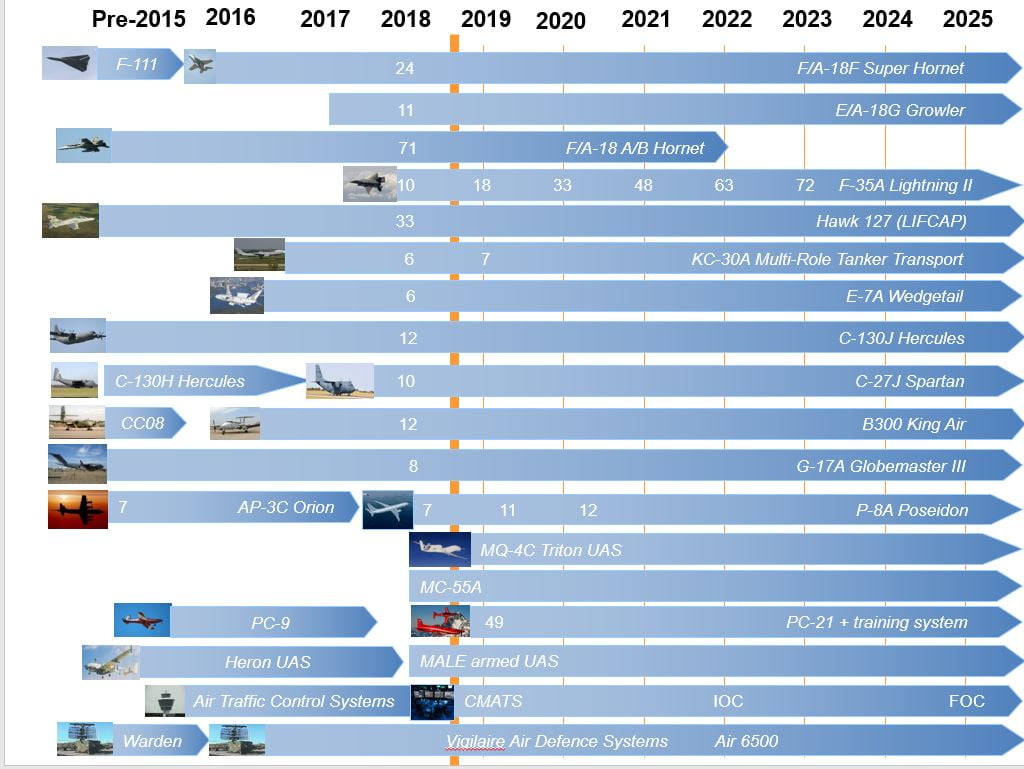

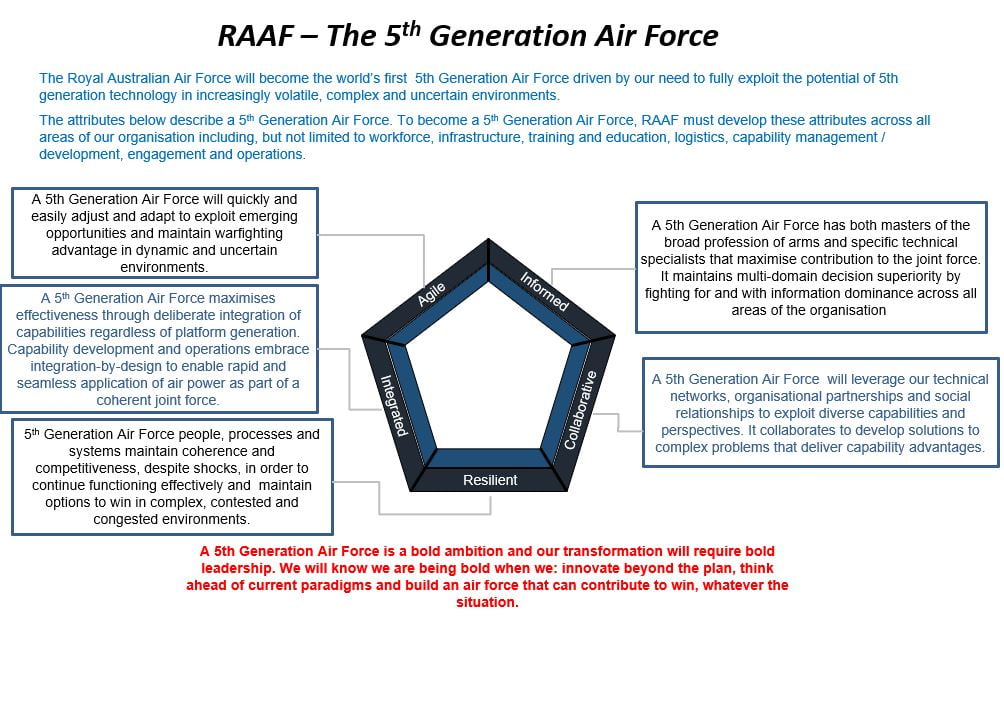

The former Chief of Staff of the RAAF, Geoff Brown, who is also the Chairman of the Williams Foundation, provided an overview of how the selection of the F-35 and its introduction in the force was part of a significant shift in the ADF to what the Aussies call a fifth-generation force.

Chatham House rules are followed by the Conference and are respected throughout this article.

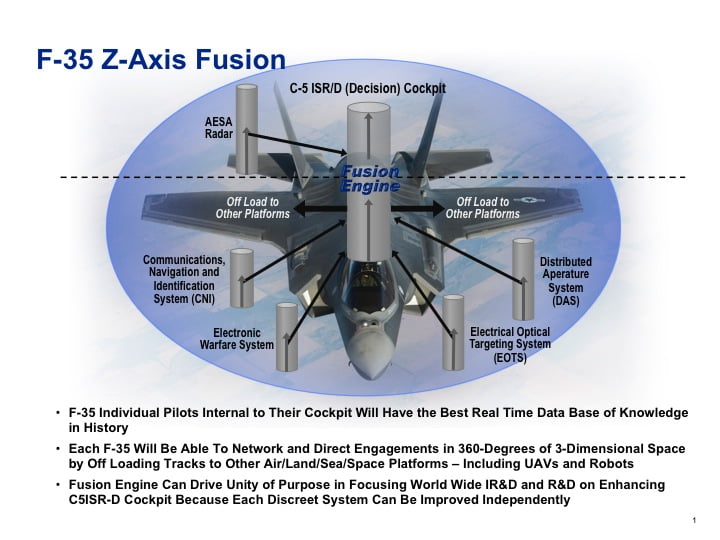

A senior USAF officer involved with F-35 integration highlighted the work of the USAF in the area of operating the aircraft and working integration both on the level of the MADL-enabled F-35 force and that force with the legacy force.

His baseline point was that the F-35 is operating globally now and that the USAF is working with its service and global partners on both the ability of the F-35 as a unique fleet to operate together as well as through its link capabilities, notably generated by the software designed and enabled CNI system to work with other assets as well.

This officer argued that it was clearly a work in progress and the “sensor fusion” of the force was in its infancy, in terms of its being informed by and driven by the F-35 as a combat aircraft.

Or to put it in his words: “The aircraft works well in terms of sensor fusion; what we are focused on in this journey to mature its effects as an air system on the overall force.”

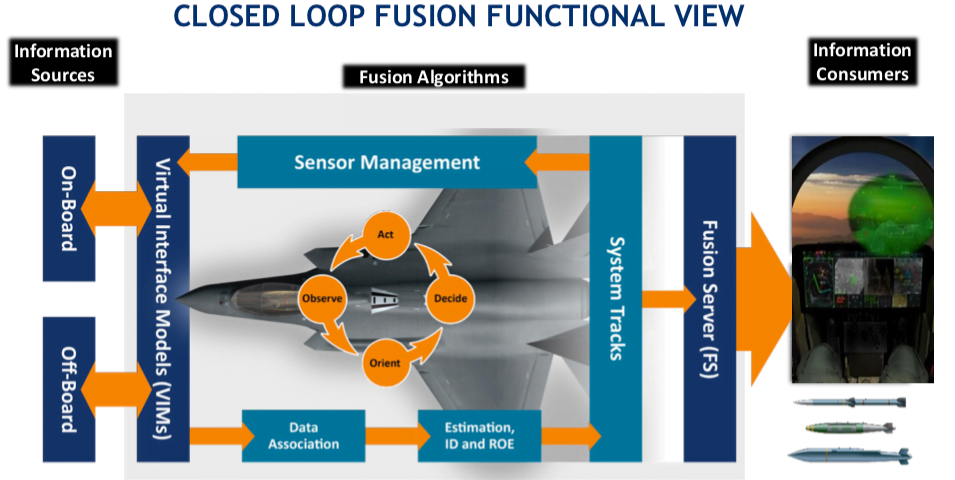

An experienced USAF test pilot, a combat proven F-16 pilot who shifted to the F-35, provided a presentation with regard to what sensor fusion means with regard to the combat pilot.

He addressed the core question: What does the situational awareness of the F-35 pilot look like and what does it mean for his combat prowess?

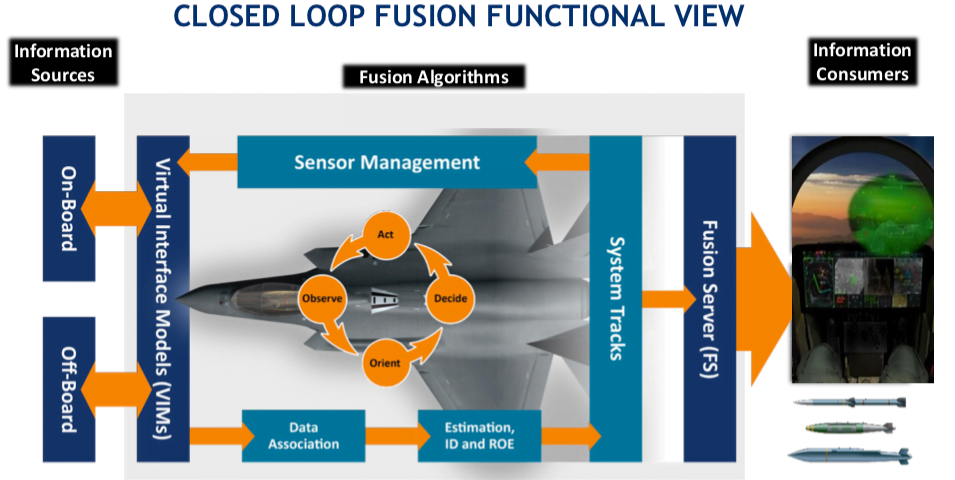

We will have a separate published interview with this pilot shortly to provide further details on this key issue but the core graphic in his presentation highlighted the F-35 and its approach to sensor fusion.

But in simple terms, the 4th generation pilot fuses the data from his systems on-board to operate up against a specific combat task.

The F-35 pilot has SA provided to him from the sensor fusion machines on-board and he focuses on shaping tasks crucial to missions in the combat space.

What is also clear is that the evolution of legacy fighters which most would refer to as fourth generation fighters is part of the evolution of the response to operating in contested airspace.

This is a major focus of attention for any of the air forces introducing the F-35 and is clearly of concern for a legacy force like the French Air Force which does not intend to buy an F-35.

There is an interesting question: How will the different legacy fleets adapt to the F-35 and what will be their tactical and strategic contributions as they adapt to the evolving strategic environment?

This question will be the focus of attention for some of our work next year, and we will publish various pieces on this issue as well as a report next year.

There is also a key dynamic of change for what are referred to as the “big wing” aircraft such as AWACS, and the various ISR aircraft.

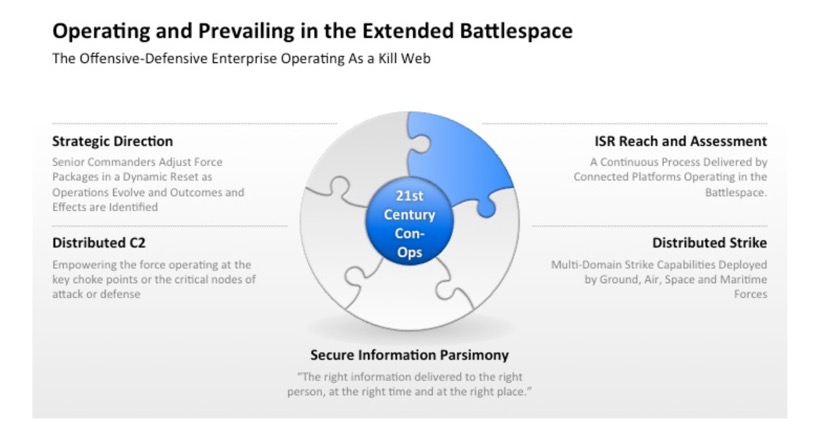

More generally, there is a major shift in how C2 will be done as fighters and their connected brethren work together to deliver the desired effects in the 21st century contested battlespace.

Several questions need to be addressed.

Where is sensor fusion done?

Where will decisions be taken with regard to determining the requisite effects and who will deliver them?

How will different air forces connect the force in distributed operations in contested airspace and with what systems and means?

And as multi-domain operations come to dominate, meaning the ability to deliver effects throughout the entire combat force with fighters playing various roles, C2, ISR, strike, how will platforms be designed going forward to enhance capabilities of the overall combat force?

The evolution of the fighters will include the F-22 as well so you have a case of a fifth-generation aircraft evolving with the introduction of the F-35 as well as the USAF’s F-16s and F-15s or the US Navy’s Super Hornets.

These adaptations will not be exactly the same and are clearly a focus of attention and discussion going forward.

Put in other terms, how will legacy aircraft evolve, as the challenge of dealing with contested airspace but also contributing to multi-domain operations becomes a primary driver of change for the air combat force?

European speakers highlighted the evolution of three legacy aircraft, the Gripen, the Rafale and the Eurofighter.

The presentations built around Gripen provided insights concerning how the fighter really has become a flying computer and how the modern fighter is evolving as part of the reconnaissance strike enterprise.

One presenter argued that the evolution of fighters more on the model of computer dynamics meant that the meaning of aircraft generations was put in question.

A senior French General highlighted the upcoming changes in the core French fighter, the Rafale, which would make it more capable, in terms of processing power and in terms of upgradeability.

He also raised concern that the coming of the F-35 to Europe and to NATO posed a significant problem of interoperability for the Rafale and he argued that this challenge needed to be met.

And this is a significant concern but also a focus of core attention at places like the European Air Group where I have engaged for many years exactly on this challenge.

The Eurofighter presenters highlighted as well the modernization of their aircraft and its expanded capabilities.

I have visited several Eurofighter bases and have discussed modernization of the aircraft with several persons involved in the process and produced a report on this effort in 2015.

I have also visited RAF Tornado squadrons as well to discuss the impact of the termination of their operations on the RAF as well.

The British evolution of their Eurofighters is called Project Centurion and encompasses changes associated with the retirement of their Tornados.

But it is also about evolving the aircraft to fly with F-35 which more generally subsume a broader range of Tornado and Harrier missions while adding some new mission capabilities as well.

There is an accompanying effort as well in the sustainment approach for the UK Eurofighters called TyTan and a visit to a key RAF airbase earlier this year provided an opportunity to discuss this approach with the architects and initial implementors of the evolving sustainment approach to the Typhoon fleet.

French and German presenters highlighted proposed modifications of the Rafale and the Eurofighter as part of a broader transformation which they refer to as the Future Combat Air System.

This program has been launched last year by the French and German governments with the Spanish as probable partners perhaps later this year or next year.

The program is designed to replace Rafale and Eurofighter by 2040, although the question of the Tornado replacement for Germany remains a question mark and a clear focus of attention and contention as well.

Does FCAS incorporate the Tornado replacement by expanding the Eurofighter fleet and waiting for the new 2040 plus fighter or not?

This is an actively debated question, which came up as well at the discussions at the conference.

The FCAS approach can be looked at two very different ways.

One way is to look at the end state as a target towards which modernization is focused.

Here the notion is that the system or the networks will be designed to provide multi-platform and multi-node capabilities to deliver the combat effects required to operate in contested airspace and to prevail in the combat areas of interest.

The focus is less on what organically can be delivered by a proposed new fighter than its ability to trigger, interact with or work with other platforms to deliver the desired combat effect.

Here the discussion encompasses as well discussions I have in Australia with regard to what is the changing relationship between platforms and systems as well as the question of how to develop new platforms in light of the evolving approach to force package integration and distributed C2 approaches and capabilities.

A second but correlated way to look at it is to shape a building process whereby key elements are identified, designed and built through the next 20 years and operationally introduced into the relevant European combat force in anticipation of the fighter to be designed through an open-ended process with the design closure affected by that learning curve.

A case in point was provided by a senior Airbus official involved in FCAS who provided a case study of what Airbus has in mind.

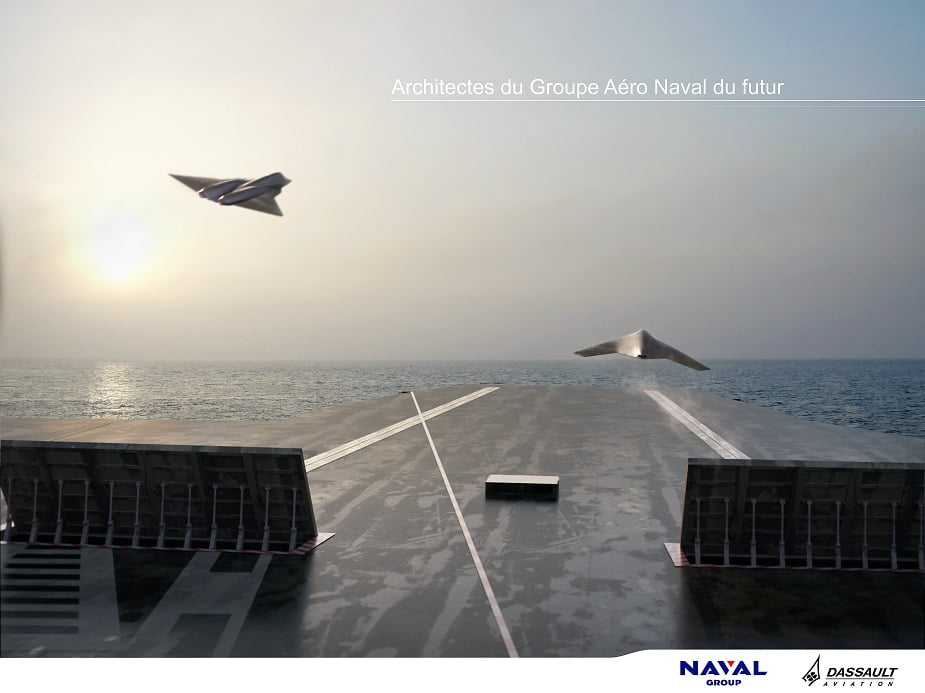

The broad point was that the manned fighter would be working in the future with remote combat systems in the combat air space and the core competence which needs to be created would be a teaming capability.

This requires developing and evolving sophisticated software and teaming concepts of operations to work with extant fighters and any future fighter.

Airbus recently did a demonstration of such a complex teaming effort over the Baltic Sea. In this experiment, the drones or remotes were given combat tasks by a combat aircraft and the drones then executed their tasks using their own autonomous systems.

What this approach might mean for Airbus is that they would generate a core software driven house working to then shape relevant (in this case) platforms which would operate with remotes in the battlespace.

In other words, the relationship between software development teams and platform designers is in the throes of an historical shift, and the focus of the FCAS project in many ways underscores recognition of this shift.

I have a separate interview with this senior Airbus official which will lay out further elements of the core approach as well which will be published later this month.

Such software driven teaming capability could be understood as a building block or a stakeholder in the FCAS fighter some years down the road.

Of course, it could be part of the overall transition being driven as the F-35 has entered and expands its presence in the European combat force as well.

In other words, the adaptations of the legacy combat fighter fleet plus the development of blocks of FCAS capability can be seen as harbingers of FCAS and as adaptations to work as the NATO fleet changes as other new capabilities come into the force.

In short, significant innovation will characterize the way ahead as peer competitors confront each other and adjust to each other’s capabilities and performance in combat.

And the decade of innovation ahead will clearly lay the foundation for the next.

The elephant in the room clearly was what would Germany do with regard to their Tornado replacement aircraft?

This replacement challenge also includes a subsumed issue with regard to any nuclear mission within which the German Air Force might participate in the period ahead.

The Germans face three choices with regard to Tornado replacement.

First, they could buy a squadron or two of F-35s which would link them as well to what the Nordics, the UK and Italy are also doing.

If they wish to continue the nuclear mission, the evolution of the F-35, Block IV of the software which is being readied now would be available to integrate nuclear weapons within the F-35.

Several German companies already are involved with the F-35 in terms of the manufacturing base for F-35 within the context of Industry 4.0.

Second, the Luftwaffe could replace Tornado with an upgraded Eurofighter, similar in some ways to what the UK has done with Project Centurion.

There are key questions of the UK working relationship with the German part of Eurofighter as there are IP and investment issues which the UK has made but the other Eurofighter partners have not.

And with Brexit looming over the Euroighter future, ways need to be navigated to shape the way ahead.

But Eurofighter has not been certified to carry nuclear weapons, and it is not clear that the US will do this, less for reasons of pique than for reasons of suitability as well.

But this is a work in progress or not.

Third, the FCAS project clearly is a long range goal for the French and German governments, but the path ahead needs to be shaped in part to find ways of convergence between the Rafale and German Eurofighter upgrades and software commonality.

Can this be done in time for the Tornado replacement?

It the goal is to replace Rafale and Eurofighter in the future with a common fighter aircraft in the 2040 time frame there is little doubt that by dovetailing efforts this can be achieved.

This requires convergence at the governmental level with regard to procurement, with convergence with regard to the two Air Forces and cultural integration among the key companies which will develop, test and build the new fighter aircraft.

As a long term goal, the key focus in the near to mid term needs to focus on the building blocks to get to the kind of integrated air combat picture highlighted by the FCAS approach.

For example, a new Airbus A320neo could be built in such a way that it is modular and FCAS enabled so to speak.

But the Luftwaffe is facing the question posed by the RAF F-35 leader: the future is now?

How does Germany address this question?

The French answer on display throughout the conference was fairly straightforward — continue the upgrade process of the Rafale which would fly in the words of on French General until 2060.

And concurrent with that upgrade and modernization process, launch the process of convergence in French and German thinking to get to an FCAS end point.

The question of the Tornado replacement either is a question which deserves an answer in and of itself, or it is mutated into Eurofighter evolution which neither the RAF nor the Italian Air Force are doing outside of the context of F-35 integration.

It is a debate and work in progress and perhaps by the next Fighter Conference there will be more clarity on these issues.

The International Fighter Conference is held by IQPC and next year’s conference will be also held in Berlin from November 12-14 2019 and if this year’s conference is anything to go by, it is highly recommended that persons interested in the evolution of the air combat force attend.

Although the focus is upon fighters, given the evolution combat, the scope is rapidly expanding to a discussion of operations in the integrated battlespace.

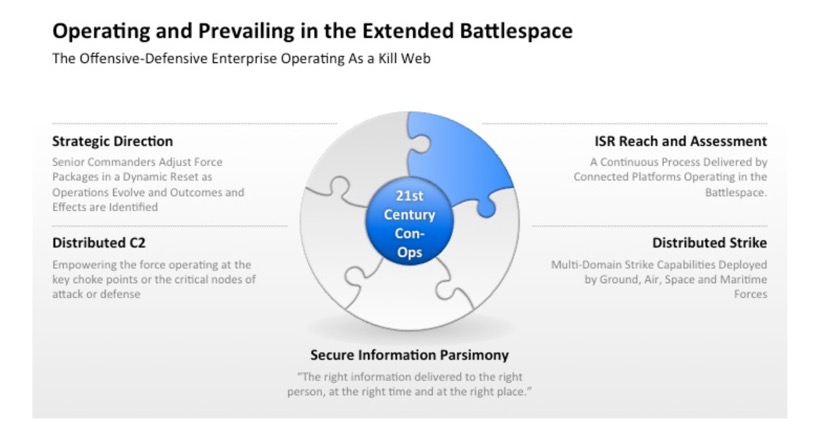

I will conclude by highlighting a graphic which I crafted during my time over the past five years engaged with The Williams Foundation looking at the evolution of the integrated combat force, in ways necessary to deal with the evolving battlespace.

The featured photo shows a German Air Force Panavia Tornado aircraft taking off over Bodo, Norway on October 26, 2018 during Exercise TRIDENT JUNCTURE 2018. Image by: Corporal Bryan Carter, 4 Wing Imaging