2017-07-28 By Robbin Laird

The coming of the F-35 provides a significant opportunity to leverage the investment efforts of core allies as is happening in the UK with 5th Gen weapons such as Meteor and SPEAR 3:

- F-35 as a global enterprise – the 9-Nation MOU encourages US allies in the program to invest in core capabilities for the benefit of the JSF partnership – Meteor and SPEAR 3 are examples of this;

- F-35 is the bedrock for high end warfare and 5th generation weapons such as Meteor/SPEAR 3 will help maximize coalition capabilities with direct benefit to the US services in the joint fight;

- The integration of 5th Gen weapons such as Meteor onto 4th Gen platforms also enables the allies to better utilize their whole combat air force, not just their 5th Gen platforms.

For the US, this path opens up a number of options; one example is the potential interoperability of UK and USMC F-35Bs afloat where jets would be able to fly from each other’s decks with whichever weapons are to hand. It could go a step further and open up a scenario where the US consider adopting these new weapons onto US F-35s, which share integrative commonality with allied F-35s.

The United States could thus leverage allied investments in the weaponization of the global F-35 in a significant way, but not if it follows a protectionist policy or continues to pursue the legacy of the most recent Administration’s legacy to often have competition for competitions sake rather than simply moving ahead with the off the shelf solution.

Allied weapons integration on the F-35 provides a range of off the shelf solution sets for the US forces, which should be leveraged. The US can put its investment into additional weapons capabilities rather than simply investing in areas already covered by advanced weapons capabilities developed and deployed by allies.

The F-35 global enterprise provides a way ahead for more rapid development of weapons, by leveraging allied investments and capabilities whilst the US develops new capabilities in parallel, which can then be offered to the allied F-35 users as well. A new business model has emerged precisely when a new Administration has arrived in Washington, which has underscored its desire for new business models.

Here one is staring them directly in the face.

There are several examples of the opportunities which represent low hanging fruit which can be leveraged.

For example, in the UK, MBDA and the three UK Armed Services have worked closely over the years, and most notably with the establishment of the Team Complex Weapons approach that has deepened their ability to work closely together.

This approach was described by MBDA as follows:

Team Complex Weapons (Team CW) defines an approach to delivering the UK’s Complex Weapons (CW) requirements in an affordable manner. This value for money proposition also ensures a viable industrial capacity.

The implementation of the Team Complex Weapon’s approach between Ministry of Defence (MoD) and MBDA is through the Portfolio Management Agreement (PMA), which has been independently evaluated as offering greater than £1Bn of benefit to MoD over their 10-year planning period.

The PMA aims to transform the way in which CW business is conducted by MoD with its main supplier. At the heart of this is a joint approach to the delivery of the required capability based on an open exchange of information and flexibility in the means of delivery.

http://www.mbda-systems.com/about-us/mission-strategy/team-complex-weapons/

This agreement has allowed the UK MoD to work with MBDA and other weapons suppliers to shape the evolution of capabilities in close cooperation with the operators to shape ongoing capabilities. And such an approach is absolutely central to the emergence of the next wave of weapons, namely software upgradeable ones. The developer, manufacturer and the operator have to be in a close symbiotic relationship to craft the kind of software transient advantage necessary to deal with peer competitors.

As the head of the USAF Materiel Command has put it with regard to software enabled weapons systems:

“The teams are there for life.

“I don’t mean that it’s one person, but we don’t think about putting a team together to do the development and then push them out the door.

“That team stays with that system forever…

“We need to make the user the operational user and acceptance authority.

https://sldinfo.com/software-upgradeability-and-combat-dominance-general-ellen-pawlikowski-looks-at-the-challenge/

The working relationships established under Team CW have facilitated the transition to the next phase of weapons development, namely software upgradeable weapons. It has also allowed for the significant evolution of capabilities to support the land wars, notably with the transition from Brimstone to Dual Mode Seeker Brimstone.

One example is clearly the Meteor missile. It is an active radar guided beyond visual range air to air missile which offers a multi-shot capability against long range maneuvering targets. It can do so in a heavy electronic countermeasures environment at extended ranges owing to its air-breathing propulsion system

The Meteor being fired by F-35B. Image credited to MBDA.

The Meteor being fired by F-35B. Image credited to MBDA.

Longer range is crucial for a combat aircraft that has enhanced situational awareness with a significantly greater radar reach than the current AMRAAM, and the Meteor certainly is considerably more appropriate than the traditional AMRAAM for the F-35.

The new Meteor missile developed by MBDA is a representative of a new generation of air combat missiles for a wide gamut of new air systems. It can be fitted on the F-35, the Eurofighter Typhoon, Rafale, Gripen and other 21st century aircraft.

It is a software upgradeable missile which pairs nicely with the arrival of a software upgradeable aircraft like the F-35.

Software upgradeability is a game changer for 21st century systems not well understood or highlighted by analysts. In the past, new products would be developed to replace older ones in a progressive but linear dynamic.

But now, one builds a core product with software upgradeability built in, and as operational experience is gained, the code is rewritten to shape new capabilities over time. Eventually, one runs out of processor power and BUS performance and needs to consider a new product, but with software upgradeability, the time when one needs to do this is moved significantly forward in time.

It also allows more rapid response to evolving threats. As threats evolve, re-programming the missiles can shape new capabilities, in this case the Meteor missile. The current production missile is believed to be using well below the maximum processing power and bus capacity of the missile. Significant upgradeability is built in from the beginning.

Although software upgradeability is not new with regard to weapon systems, the F-35 as software upgradeability is. Combining the launch of a software upgradeable aircraft with a missile designed from the ground up with upgradeability built in will allow the aircraft and the weapon to evolve together over time to deal with evolving threats and challenges.

And underlying the model and the code is a multinational team. And this team is the core capability, which can drive weapons development over time. MBDA has functioned as the prime and has worked with three aircraft manufacturers and radar manufacturers already and is working with additional players as the missile prepares to go onto the F-35.

What has been a challenge – working with six air forces – is an opportunity as well. Each of the partners had different takes on the target set they wished the missile to serve. This has meant that the range of targets and engagement envelopes were very wide ranging, from low-level cruise missiles and high flyers, to UAVs, to helos, etc. The end result is a software upgradeable missile with a very wide-ranging initial capability to deal with a diversity of targets.

Another key aspect of the missile is it is designed from the beginning to be employed on and off-board. It can be fired by one aircraft against a target initially cued by another aircraft or system and then handed over for delivery to target by the original aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target.

It is understood the missile will be integrated into the Block 4 of F-35. When so done, the missile can provide a sweet spot of 4th and 5th generation weapons integration with its core networking capability. Because of the nature of software integration on the F-35, the Meteor missile, which will be integrated onto the F-35 due to European requirements, means that it is available to all the other global partners of the F-35 as well.

The RAF Typhoon Force is leveraging Meteor as a key asset to work integration with the F-35.

The Typhoon is being modified to enhance its capability to receive targeting data from F-35s and with the longer range of the Meteor can operate as a weapons caddy for the F-35 in firing many types of weapons, and certainly provide a significant barrage of air to air strike missiles to support the forward operations of the F-35.

https://sldinfo.com/building-a-21st-century-weapon-the-case-of-the-meteor-missile/

Training is already underway for this transition and interviews with RAF pilots recently involved in Red Flag and Green Flag exercises in the United States highlighted the evolving RAF thinking.

Shaping a new weapons revolution where weapons are enabled throughout the attack and defense enterprise and not simply resident for organic platform operations is a key element of the way ahead. For example, the new software enabled Meteor missile can be fired by one aircraft and delivered to target by that aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target. METEOR firing from Gripen. Credit: SAAB

Shaping a new weapons revolution where weapons are enabled throughout the attack and defense enterprise and not simply resident for organic platform operations is a key element of the way ahead. For example, the new software enabled Meteor missile can be fired by one aircraft and delivered to target by that aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target. METEOR firing from Gripen. Credit: SAAB

With regard to Red Flag 17-1, Wing Commander Billy Cooper, the 6th Squadron Typhoon commander had this to say about the way ahead:

“If you optimize the relationship between fourth and fifth-gen would want your 4th gen as far from harm as possible, especially given the low observable nature of the 5th gen platforms.

“In the air to air war you would therefore want to have the longest-range weapons you could on your 4th gen platforms.

“That is where Typhoon and Meteor comes in; I really do think it will be a game-changer in the 4th/5th Gen war.”

https://sldinfo.com/red-flag-2017-1-the-perspective-of-the-6-squadron-officer-commanding/

And the Squadron Leader for II(AC) squadron based on his recent experience at Green Flag argued that a robust weaponization approach was necessary to leverage the capabilities being shaped by the 5th generation enabled air combat force.

“Weaponization of the Typhoon has been fairly well defined over the last ten years.

“Everyone’s known what the integration periods are going to be for which weapons.

“One thing that we just have to keep re-assessing as that process goes on is that are these actually the right weapons for the task that the jet is going to be asked to deliver?

“Should we add weapons for SEAD missions for example, as the F-35 becomes the forward deployed task master for such missions, aided significantly by strike assets from Typhoon?

“We need to ensure that we are not hamstringing ourselves with the weaponization process.

“We need to open the aperture as we reshape the air combat fast jet force.”

And as this process evolves the integration to other non-air assets becomes crucial as well, whether it is integration with naval assets from a strike or ISR/C2 point of view.

“We’ve built new Type 45 destroyers and are building new CVF Aircraft carriers and Type 26 Destroyers.

“The information soak from F-35 has to be taken into account as those new assets come into service.

“Are we utilizing that information in its best available capacity?

“It is way beyond ownership of one or the other service; it is about having an integrated combat force.”

https://sldinfo.com/visiting-iiac-squadron-at-raf-lossiemouth-the-perspective-of-squadron-leader-martin-pert/

Maximizing effective use of U.S. and allied weapons investments is crucial to accelerate the transition from the land wars to enhanced air combat power for higher intensity and higher tempo operations.

And clearly Brimstone and Spear 3 are very relevant to current and evolving US needs. It is difficult to understand why the US would not adopt this weapon and include it in its own combat capability arsenal as a complement to its other weapons such as SDB 2.

During a recent visit to RAF Lossiemouth, this is what a weapons officer had to say about the RAF experience with Brimstone.

“We first put the weapon into use a decade ago and it has become a weapon of choice for the RAF and for our allies in tasking the RAF as well.

“It enhanced the capability of the Tornado and what it could do in areas like Afghanistan.

“It became a more precise weapon and you could target individual houses, cars, moving targets, or even people with the weapon.”

https://sldinfo.com/weapons-in-the-tornado-typhoon-transition-shaping-a-way-ahead/

Not only is Brimstone available now for the US air combat fleet, and it can be suggested as well, that it is not simply fast jets which could use this capability but other airborne platforms as well (it is believed that the UK plans to integrate Brimstone on Protector and its AH-64 too) but the Spear 3 follow on weapon will be integrated onto F-35 and available for the US forces almost as an app.

According to MBDA in an article published in Air Power 2017:

The need for greater range and capability in the air-to-ground mission has been recognised for a number of years. Most direct fire weapons have relatively short range and the array of glide bomb weapons are not providing adequate time to target, time on target and end-game performance capabilities – let alone the range – needed to defeat existing and emerging Ground Based Air Defence systems.

For this reason there is significant focus on developing systems that can defeat the increasing threats.

MBDA’s SPEAR air-to-ground precision strike weapon will meet this growing operational demand. Utilising and building on the best key technologies from the combat proven Brimstone weapon, SPEAR is being developed to meet the requirements for a multi-load out missile system for operation from fixed wing aircraft. Initially the weapon will be deployed on the UK’s Royal Air Force and Royal Navy F-35 fleet.

Artist Rendition of F-35 Firing Spear 3 Missile. CreditL MBDA

Artist Rendition of F-35 Firing Spear 3 Missile. CreditL MBDA

For F-35, the weapon will be mounted on a launcher that will enable four munitions to be carried in each bay alongside another weapon such as Meteor. SPEAR is equipped with a multi-spectral seeker, linked with a multiple-effects warhead.

Where SPEAR differs from glide weapons is that MBDA has equipped SPEAR with a small turbojet motor, along with its sophisticated guidance system, wing kit and actuators. The turbojet is a key benefit, providing the warfighter with significant advantages when deploying the weapon.

The weaknesses of glide weapons are that they tend to be operated in near line of sight and any deviation / off bore sight launch reduces their range. Additionally, as glide bombs are unpowered, any adverse wind or weather conditions also dramatically reduce their range. Their lower speed, agility and range rapidly reduces the realistic engagement options for the pilot.

Time critical targets also become a challenge for glide weapons – they are simply too slow to meet the needs of the modern battlefield. SPEAR’s range capability in any weather conditions is unmatched, as is its seeker accuracy and performance against moving targets.

SPEAR has already concluded extensive and successful subsystems and airframe proving demonstrations for the UK MoD customer.

For example in the Spring of 2016, a SPEAR missile was launched from a Eurofighter Typhoon aircraft deployed from the BAE Systems facility at Warton, UK. The aircraft was flown to the QinetiQ range at Aberporth where SPEAR was successfully deployed. SPEAR is carried upside down so at launch the missile must turn over, then deploy its wings, start the jet engine and then navigate a course to target. All these operations were successfully demonstrated during the trial.

http://ow.ly/Xae730dzsbz

Spear 3 is a natural for the USMC concepts of operations and its closest partner, the UK, will have already done its integration. The new business model would suggest that the USMC and USN should seriously consider acquiring this weapon for the relevant mission sets.

Recently, Defence Minister Fallon suggested that the UK’s openness to acquiring US weapon systems needs to be reciprocated by the United States. But the new F-35 business model goes beyond the simple question of classic protectionism or conducting costly but meaningless competition when an off the shelf allied solution is already in play.

Put bluntly, the F-35 business model rests on leveraging joint investments and capabilities. For the United States not to follow the F-35 business model would suggest that the business rules followed by DoD simply are not capable of adjusting to the new 21st century realities of business.

And the Trump Administration can not really want to see such lack of innovation, an innovation generated by the new combat capability which the US has invested so much in itself.

And the UK investments and operational efforts to integrate UK weapons onto the RAF/RN F-35s is clear and significant. The UK will integrate Paveway 4, Meteor, SPEAR 3 and ASRAAM to the ‘B’ variant aircraft and be operational with these weapons by c. 2023. It simply remains for the US to pursue the logic of the F-35 business model.

Editor’s Notes: Recent updates on the evolution of MBDA systems are provided below.

http://www.baesystems.com/en/article/successful-completion-of-first-live-firing-of-brimstone-missile#

The first live firing of MBDA’s Brimstone air-to-surface missile from a Eurofighter Typhoon has been successfully completed as part of ongoing development work to significantly upgrade the capability of the aircraft. The trial is part of work to integrate the Phase 3 Enhancement (P3E) package for Typhoon, which will also deliver further sensor and mission system upgrades.

The P3E package forms part of Project Centurion – the programme to ensure a smooth transition of Tornado GR4 capabilities on to Typhoon for the Royal Air Force.

The UK’s IPA (Instrumented Production Aircraft) 6 Typhoon conducted the firing with support from the UK Ministry of Defence, MBDA, QinetiQ, Eurofighter GmbH and the Eurofighter Partner Companies – Airbus and Leonardo. It was designed to test the separation of the low-collateral, high-precision Brimstone weapon when it is released.

In total, nine firings will take place to expand the launch and range capabilities.

The initial firing follows completion of a series of around 40 flight trials earlier this year, some of them conducted alongside pilots from the Royal Air Force’s 41(R) Squadron – the Test and Evaluation Squadron – in a Combined Test Team approach.

Volker Paltzo, CEO for Eurofighter Jagdflugzeug GmbH, said: “The successful completion of this trial is an important step towards integration of the weapon on to the aircraft. Brimstone will provide the Typhoon pilot with the ability to precisely attack fast-moving targets at range, further enhancing the aircraft’s already highly potent air-to-surface capabilities.”

Andy Flynn, BAE Systems Eurofighter Capability Delivery Director, added: “Through the dedicated work of our teams, and with support from our partners, we have been able to reach this milestone in a short space of time. We will now continue to work alongside the Royal Air Force and our partner companies in a joint approach to ensure we successfully deliver this package of enhancements into service.”

Andy Bradford, MBDA Director of Typhoon Integration, said: “This first firing is a major milestone for both the Brimstone and Typhoon programmes. Together Brimstone and Typhoon will provide the Royal Air Force and other Eurofighter nations with a world-beating strike capability to beyond 2040.”

The successful trial follows completion earlier this year of the flight trials programme for the MBDA Storm Shadow deep strike air-to-surface weapon and the MBDA Meteor ‘beyond visual range’ air-to-air missile. Operational testing and evaluation of those capabilities is currently ongoing with the Royal Air Force ahead of entry into service in 2018.

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-secretary-announces-539-million-investment-in-new-missiles-systems

Secretary of State, Sir Michael Fallon, has today announced three new missile contracts worth a combined £539 million for state-of-the-art Meteor, Common Anti-air Modular Missile (CAMM) and Sea Viper missile systems at MBDA Stevenage.

The deal ensures our Armed Forces have the best equipment available to protect the new Queen Elizabeth Class Carriers and the extended fleet from current and future threats.

The half a billion-pound contracts will sustain over 130 jobs with MBDA in the UK, with missile modification and service support being carried out in Stevenage, Henlow, Bristol and Bolton.

Secretary of State, Sir Michael Fallon, said:

“This substantial investment in missile systems is vital in protecting our ships and planes from the most complex global threats as our Armed Forces keep the UK safe.

“Backed by our rising Defence budget, these contracts will sustain high skilled jobs across the UK and demonstrate that strong defence and a strong economy go hand in hand.”

As part of a £41 million contract, the Meteor air-to-air missiles will arm the UK’s F-35B Lightning II squadrons. It will provide the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy with a world-beating missile that can engage with targets moving at huge speed and at a very long range. The weapon will enter service on Typhoon with the RAF in 2018 and the F-35B from 2024, and will be used on a range of missions including protecting the Queen Elizabeth Class Carriers.

Meanwhile, a £175 million in-service support contract for the anti-air Sea Viper weapon system will ensure that the Royal Navy’s Type 45 Destroyers can continue to provide unparalleled protection from air attack to the extended fleet. Under the contract, the missiles will be maintained, repaired and overhauled as and when required to ensure continued capability. The Sea Viper missile defends ships against multiple threats, including missiles and fighter aircraft.

The final contract is a £323 million deal to purchase the next batch of cutting-edge air defence missiles for the British Army and Royal Navy, offering increased capability at a lower cost. Designed and manufactured by MBDA UK at sites in Bolton, Stevenage and Henlow, the next-generation CAMM missile will provide the Armed Forces with missiles for use on sea and on land. CAMM has the capability to defend against anti-ship cruise missiles, aircraft and other highly sophisticated threats.

Signalling our continued investment in Type 26 programme, CAMM will provide the anti-air defence capability on the new Type 26 Frigates for the Royal Navy and will also form part of the Sea Ceptor weapon system on the Type 23 Frigate and will also enhance the British Army’s Ground Based Air Defence capability by replacing the in-service Rapier system.

Tony Douglas, Chief Executive Officer of Defence Equipment and Support, the MOD’s procurement organisation, said:

“Work on these cutting-edge missiles, which will help to protect the UK at home and abroad and secure jobs across the country, demonstrates the importance of Defence investment. That is why, working closely with our industry partners, we continue to drive innovation and value into everything we do; securing next generation equipment for our Armed Forces at the best possible value for the taxpayer.”

Dave Armstrong, Managing Director of MBDA UK, added:

“MBDA is delighted by the continued trust placed in us by the Ministry of Defence and the British military. The contracts announced today for Meteor, CAMM and Sea Viper will help protect all three UK Armed Services, providing them with new cutting-edge capabilities and ensuring their current systems remain relevant for the future. They will also help to secure hundreds of high-skilled people at MBDA UK and in the UK supply chain, maintaining the UK’s manufacturing base and providing us with a platform for exports.”

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/mod-signs-184-million-contract-to-secure-air-to-air-missiles-for-the-f-35

The Ministry of Defence (MOD) has awarded a contract worth around £184 million to ensure the UK’s new supersonic stealth combat aircraft will continue to be equipped with the latest air-to-air missile.

Designed and manufactured in the UK, ASRAAM is an advanced heat-seeking weapon which will give Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy F-35B Lightning II pilots, operating from land and the UK’s two new aircraft carriers, the ability to defeat current and future air adversaries.

The contract is just the latest demonstration of the Government’s commitment to ensuring the Armed Forces have the best possible equipment and aircraft equipped with ASRAAM will operate from land as well as from the Royal Navy’s two new aircraft carriers, the biggest ships ever to be built for the Navy.

It will see MBDA manufacture an additional stockpile of an updated version of the weapon, allowing F-35 combat jets to use the missile beyond 2022. Work to integrate the new missile onto the UK’s F-35 fleet will be carried out under a separate contract.

Minister for Defence Procurement, Harriett Baldwin said:

“Wholly designed and built in the UK, this air-to-air missile on our F-35 aircraft will secure cutting-edge air power for the UK for years to come.

“This contract will sustain around 400 jobs across the country and is part of the MOD’s £178 billion Equipment Plan which is backed by a defence budget that will increase every year from now until the end of the decade.”

The award is part of an overarching agreement with MBDA which is sustaining around 200 jobs at the company’s sites in Bristol, Stevenage and Bolton, with a further 200 sustained across the supply chain. Work on ASRAAM will be carried out at MBDA’s new, £40 million state of the art manufacturing facility that is nearing completion in the Logistic North commercial development in Bolton.

MBDA’s investment in this new facility is a demonstration of the company’s commitment to maintaining highly skilled engineering jobs in the region as well as to providing the very best equipment required by the UK’s armed forces. The award of the contract to MBDA underlines the Government’s commitment to sustaining a cutting edge defence industry in the UK.

ASRAAM, which uses a sophisticated infra-red seeker, is designed to enable UK pilots to engage and defend themselves against other aircraft.

It is capable of engaging hostile air targets ranging in size from large multi-engined aircraft to small drones.

Chief Executive Officer at the MOD’s Defence Equipment and Support organisation, Tony Douglas said:

“ASRAAM will provide vital offensive and defensive options for UK F-35 pilots against a wide range of air-to-air threats.

“The project to update the weapon and integrate it with the F-35, the world’s most advanced combat aircraft, provides a clear example of the MOD and UK industry working effectively together to provide our UK Armed Forces with the best equipment possible.”

ASRAAM is currently in service with RAF Typhoon and Tornado aircraft and is being carried daily on missions over Iraq and Syria as part of the coalition fight against Daesh.

The updated missile variant being secured under this new contract is expected to enter service on RAF Typhoon aircraft from 2018 and on RAF and Royal Navy F-35 aircraft from 2022, when the current variant will be taken out of service.

With the biggest defence budget in Europe and the second biggest in NATO the Government is investing in new aircraft carriers, submarines, warships and patrol vessels.

http://www.mbda-systems.com/press-releases/bruiser-loose-successful-first-firing-mbdas-sea-venom-anl/

MBDA’s Sea Venom / ANL anti-ship missile has successfully completed its first firing at the Île du Levant test range in France.

Conducted in June, the first firing is a major milestone for the Anglo-French missile; developed to deliver an enhanced capability and replace existing and legacy systems such as the UK-developed Sea Skua and the French-developed AS15TT anti-ship missiles.

The trial of the 100 kg-class missile was conducted from a Dauphin test bed helicopter owned by the DGA(Direction Générale de l’Armement – the French defence procurement agency).

Frank Bastart, head of the Sea Venom/ANL programme at MBDA, said: “The missile trial was a complete success, and is a proud moment for the company and all those involved in the project. When it enters service Sea Venom/ANL will provide a major increase in capability to the French and UK armed forces.”

Jointly ordered in 2014, the Sea Venom/ANL project has been developed 50/50 between the UK and France and has played a key part in the creation of shared centres of excellence on missile technologies in both countries – a move that will provide significant benefits to both nations.

Paul Goodwin, deputy head of the Sea Venom project, added: “Although a first firing this was in no way a cautious one. The system was pushed to the very edge of its range capability – a bold step showing our confidence in the design maturity and making success all the more sweet. The next step is to exercise the systems’ operator-in-the-loop capabilities.”

In UK service the missile is planned to be used from the AW159 Wildcat helicopter, while France will operate the missile from its new Hélicoptère Interarmées Léger (HIL). The missile has been designed for use from the widest range of platforms, with air carriage trials having been conducted to demonstrate compatibility of the missile on legacy Lynx helicopters.

https://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/f-35-firing-boosts-asraam-sales-prospects-435233/

F-35 firing boosts ASRAAM sales prospects

Lockheed Martin F-35s have fired their first non-US-produced missiles in testing, with the activity providing a boost to MBDA’s sales efforts for the ASRAAM.

Announcing the development on 15 March, MBDA said flight trials and air-launched firings have taken place using test aircraft operating from Edwards AFB, California and NAS Patuxent River, Maryland.

The short-range, infrared-guided ASRAAM is being integrated with the short take-off and vertical landing F-35B variant for the UK. “The effort is progressing to plan, and these integration activities will allow the initial operating capability of the aircraft” for the nation, MBDA says.

The European company hopes that other F-35 customers could opt to acquire its weapon, in preference to the Raytheon AIM-9X. Australia already uses the Mach 3-capable missile on its Boeing F/A-18A/B strike aircraft, and has previously expressed some interest in also using it with its Joint Strike Fighters.

“The fact that it is a real firing that has taken place is important, because that allows the other F-35A and B users to now have a choice,” says Dave Armstrong, MBDA’s executive group director for sales and business development.

Meanwhile, Armstrong says the company remains hopeful that the US military could acquire its Brimstone air-to-surface missile to provide some of its fast jet platforms with an “off-the-shelf” precision strike capability against moving targets, despite the business uncertainty raised by US President Donald Trump’s buy-American agenda.

“We know that the US military still aspires to have Brimstone on [Boeing] F-15 and F-18,” he says. “It’s a question of economics and programme management….”

Editor’s Note: For the Joint Strike Missile case, see the following:

Allies, Missiles and the F-35: The Case of the Joint Strike Missile

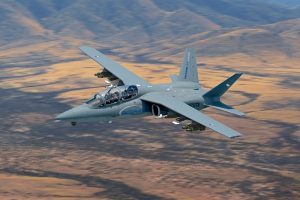

Scorpion jet multi-mission aircraft. Credit: Textron Aircraft

Scorpion jet multi-mission aircraft. Credit: Textron Aircraft

Lt. General Michael Hood assumed command of the Royal Canadian Air Force in 2015.

Lt. General Michael Hood assumed command of the Royal Canadian Air Force in 2015. CP-140 Aurora. Credit: RCAF

CP-140 Aurora. Credit: RCAF Canada’s CH-148 Cyclone maritime helicopters are now well into test and evaluation. Crews are reportedly impressed with their anti-submarine and above-water warfare suites. MCpl Jennifer Kusche Photo

Canada’s CH-148 Cyclone maritime helicopters are now well into test and evaluation. Crews are reportedly impressed with their anti-submarine and above-water warfare suites. MCpl Jennifer Kusche Photo This is a notional rendering of the 10 and 2 O’Clock challenge. It is credited to Second Line of Defense and not in any way an official rendering by any agency of the US government. It is meant for illustration purposes only.

This is a notional rendering of the 10 and 2 O’Clock challenge. It is credited to Second Line of Defense and not in any way an official rendering by any agency of the US government. It is meant for illustration purposes only.

The Meteor being fired by F-35B. Image credited to MBDA.

The Meteor being fired by F-35B. Image credited to MBDA. Shaping a new weapons revolution where weapons are enabled throughout the attack and defense enterprise and not simply resident for organic platform operations is a key element of the way ahead. For example, the new software enabled Meteor missile can be fired by one aircraft and delivered to target by that aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target. METEOR firing from Gripen. Credit: SAAB

Shaping a new weapons revolution where weapons are enabled throughout the attack and defense enterprise and not simply resident for organic platform operations is a key element of the way ahead. For example, the new software enabled Meteor missile can be fired by one aircraft and delivered to target by that aircraft or the inflight data link can be used via another asset – air or ground based – to guide it to target. METEOR firing from Gripen. Credit: SAAB Artist Rendition of F-35 Firing Spear 3 Missile. CreditL MBDA

Artist Rendition of F-35 Firing Spear 3 Missile. CreditL MBDA